This is what my life used to feel like.

I was always in a rush.

Always cutting it fine.

Often running late.

I was late for class.

Late for dinner at friends’ houses.

Late for meetings.

In my world, being late was the norm. It was perfectly acceptable to drag your feet and rock up an hour late to an event.

So, I had to learn the hard way.

One morning, I was running late for school. I rocked up to form room three minutes late, and I knew straight away I was in trouble.

My form room teacher said:

“Jane, go to student services to get a late note. You’ve been late too many times. It’s not good enough”.

When you were told to go to student services, this was bad news. You were being told to do the walk of shame.

I pleaded with her:

“Please, no! Come on! It was my dad’s fault. He was late in driving me to school. My dad is always running late”.

My form room teacher wasn’t buying my excuses.

To this day, I can still remember that walk to student services. I felt frustrated and stressed out of my mind.

It wasn’t fun being late all the time. I wanted to be on time and feel less rushed and more in control. But I had no idea how to break this bad habit.

One thing was clear to me: people weren’t happy when I was late. People would get annoyed. Passive aggressive vibes were always coming my way.

Fast forward 20 years: I’m no longer someone who is always running late and rushing around. I’m certainly not perfect, but I can say I’ve come a long way.

From my experience, I can tell you it’s exhausting being someone who is always running late for things. When you live like this, you add so much unnecessary stress, drama, and anxiety to your day.

Your days take on a frenetic feel as you rush from one thing to the next.

But there’s also a larger cost to society.

This is what the famous Good Samaritan study examined. It looked at how being rushed and time pressured impacted people’s behaviour and thought processes.

In this fascinating study, researchers conducted a psychological experiment with a group of theology students who were training to be church ministers. This was one of those psychological experiments where participants were deceived (they were told the researchers were studying one thing when they were studying something else). Here’s what happened . . .

The participants were told they were participating in a study on jobs for theology students and were asked to fill in some questionnaires (this was the bogus part of the experiment).

The real experiment took part in the next phase . . .

After the questionnaires were filled in, the participants were told they had to deliver a presentation in another university building, which was a short walk away. The students were instructed they would need to tell the story of the Good Samaritan (a story about a Samaritan who helps a stranger who has been robbed, beaten up by bandits and left half dead).

They were handed a map and provided instructions on how to get to the building, which involved passing through a dim, dingy, and drab alley.

Students were placed in one of three groups:

• High-hurry group

• Intermediate-hurry group

• Low-hurry group

After they were handed the map, the students in the high-hurry condition were told:

“Oh, you’re late. They were expecting you a few minutes ago. We’d better get moving. The assistant should be waiting for you, so you’d better hurry. It shouldn’t take but just a minute.”

Students in the intermediate-hurry group were told:

“The assistant is ready for you, so please go right over.”

Students in the low-hurry group were told:

“It’ll be a few minutes before they’re ready for you, but you might as well head on over. If you have to wait over there, it shouldn’t be long.”

While the participants walked to the building where they’d be delivering the Good Samaritan story, they encountered a slumped victim in the alley. This victim was a plant by the researchers.

The victim was an actor who was pretending to be someone in need of help. The actor wore shabby clothes and was slumped in the doorway with his head down and eyes closed. He wasn’t moving.

All the students encountered this actor. As the students walked past, the actor coughed twice and groaned (you couldn’t miss him!).

The participants didn’t know that their behaviour was under surveillance. The researchers observed how the students in each group responded to the actor. Did the participants help the man slumped in the doorway? And if so, how did they help?

Here’s what they found . . .

Low-hurry group: 63% offered help

Intermediate-hurry group: 45% offered help

High-hurry group: 10% offered help

The researchers concluded:

“A person not in a hurry may stop and offer help to a person in distress. A person in a hurry is likely to keep going. Ironically, he is likely to keep going even if he is hurrying to speak on the parable of the Good Samaritan, thus inadvertently confirming the point of the parable. (Indeed, on several occasions, a seminary student going to give his talk on the parable of the Good Samaritan literally stepped over the victim as he hurried on his way!).”

As an aside, after the experiment, the participants took part in a debriefing session where they were told what the research was actually about. The researchers made it clear that they were studying the social forces (i.e. the conditions) a person finds themselves in, and they were not passing judgment on the students’ behaviour.

In life, we can’t always control the conditions we find ourselves in (e.g., a workplace that imposes a ridiculous workload on staff). But some things are often within our control that we can do something about to be less rushed and time pressured.

Doing these things can help us to feel more present, have greater awareness of our surroundings, feel calmer and less stressed, and experience more control of our time.

I’m going to share with you some habits, ideas, and practices you can implement to help you in this area. I’ll start with the simplest habits before progressing to the deeper, more complex practices.

One of the best tools you can buy is a basic watch (preferably one that doesn’t have fancy features like the ability to receive calls or texts).

My advice is to wear a watch and look at it regularly.

A lot of people use their phones to check the time, but this can be a time trap (I find my phone way too distracting).

You may look at your phone to check the time but find yourself checking social media while you’re at it. Without any stopping mechanisms in place, you can get sucked in and thrown completely off course.

Tiny Habit:When I wake up in the morning, I will put on my watch.

When I get distracted, I will check my watch and schedule and ask “What do I need to be doing right now?”

The modern world is a distracting place. Even without access to your phone, it’s easy to get derailed. Along with checking your watch regularly, check your timetable/planner/to-do list. Ask the following questions:

• What do I need to be doing right now?

• Am I doing what I need to be doing?

• Is this the best use of my precious time and energy?

Tiny Habit:When I notice I am wasting time, I will look at my to-do list.

A prompt is a reminder. It’s anything that triggers you to move from one task or place to another.

When I need to be somewhere by a certain time, I set my alarm for when I need to leave the house. When I hear the alarm, I grab my bag and take off. No excuses.

You should have a rough idea of how long it takes to get to school or work. Set your alarm for when you need to leave. When you hear your alarm, get moving.

Tiny Habit:

When I hear my alarm, I will pick up my bag and go.

It’s tempting to cram in a few more tasks before you leave for work or school (e.g., sending one more text or watching one more short video). But ask yourself, “Do I have time to do this?”

The answer is most likely no.

Tiny Habit:When I feel tempted to do another task, I will ask “Do I have time to do this?”

When I was a kid, there was no Internet and no smartphones. But we had morning cartoons on the TV.

These cartoons were fun to watch and could easily capture your attention. But you still had some awareness of the time because the time was always displayed in the corner of the screen.

The major problem with most social media apps is they don’t contain clear time cues. This is a deliberate design decision. They want you to lose track of time. Thirty minutes online can feel like three minutes.

The solution is to stay offline in the mornings. If you must go online, have a strict log-off time. I recommend setting an electronic timer for a set time or using an Internet Blocker app to kick you off.

I use an Internet blocker app called Freedom. This app cost me a bit of money but there’s a free alternative called Cold Turkey.

Tiny Habit:

When I feel the urge to go on social media in the morning, I will set a timer for 5 minutes.

Are you feeling time pressured and running late because you’re trying to do way too much?

Our modern culture encourages us to do more, be more, have more, sleep less, etc. It’s not healthy or sustainable.

If this is the case for you (i.e. you’re overcommitted), I realise it may not be your fault. Maybe your boss or teachers have unrealistic expectations about what you can accomplish in a day.

All that being said, your packed schedule may also be due to your inability to say no. Perhaps you feel like you need to say yes to every opportunity that comes your way to build an impressive resume and stand out from the crowd. If so, I get it (I’ve been there).

The major problem with doing too much is it leaves you feeling exhausted. You’re not able to fully engage in the task. As you do the activity, you’re worrying about the next thing you need to do.

If you’re doing a bunch of stuff and not enjoying it, perhaps it’s time to cut back on a few activities.

When you commit to doing less stuff (but more meaningful activities that align with your values), you can do that stuff better. You can also extract a lot more joy from the process.

Tiny Habit:

When I am presented with a new opportunity, I will ask “Is this important to me? Is it something I want to be doing with my time?”

In the book Excellent Advice for Living: Wisdom I Wish I’d Known Earlier, Kevin Kelly states:

“You don’t need more time because you already have all the time you will ever get; you need more focus”.

If you find yourself getting distracted by social media apps and YouTube, it’s time to double down on developing your focus muscles.

You can develop your focus muscles by adopting several different habits that relate to the food you put in your mouth, incorporating regular movement and rest breaks into your day, and creating a focus-friendly environment.

This is an area I’ve been working on for a while. What I’ve noticed is when I focus my mind on one task at a time, I can get twice as much done in the time I have available. But I also find that I enjoy the process a lot more, too.

Tiny Habits:

After I stand on my office mat, I will put away three objects on my desk (removing visual clutter)

When I notice my phone is on my desk, I will pick it up and put it in another room.

After I finish doing a deep work sprint (45 minutes), I will do some gentle shoulder rolls.

These habits may sound lame and boring, but they can inject a sense of power, control, ease and even happiness into your day.

When you’re less rushed, you’re less stressed. Because you’re less stressed, the people around you are also more likely to be less stressed (calm is contagious). It also means we end up with a more helpful and thoughtful society.

In our modern world, where we find ourselves increasingly polarised and tribalised, being less rushed and time pressured is something worth striving for.

Share This:

But how much time do you actually have?

It’s hard to get a sense just by thinking “My exam is in three weeks.” After all, three weeks sounds like plenty of time, right?

Don’t be fooled. This is your brain playing tricks on you.

No one ever has a full three weeks (504 hours) to prepare for an exam. Thrown into the mix is time for sleep, getting ready for school or work, working on assignments, socialising with friends and family, etc. Plus, you usually have more than one exam to study for.

But we can forget this. And when we do, we end up procrastinating with our work and it piles up for our future selves to deal with.

What’s missing is that your brain needs clear visual feedback. It needs to have a sense of the big picture (i.e., all your commitments laid out in front of it).

By using a year-at-a-glance calendar.

Earlier this year, I printed out a massive year-at-a-glance calendar (A0 size).

I scheduled all my upcoming presentations, holidays, important events (e.g., birthdays), deadlines, etc., onto the calendar and placed it in a prime position where I couldn’t miss it.

This calendar has made all the difference. It grounds me in reality, helps me feel more in control of my schedule, and gives me clear visual feedback. It also makes me think twice before I agree to take on a new project.

In the past, whenever I’ve said yes to a new opportunity, I haven’t always been grounded in reality. Too many times, I’ve been unintentionally cruel to future Jane.

Let me explain . . .

Back in 2016, I was on the home stretch with my PhD. The path forward was clear. After years of struggling with my PhD, the end was in sight. I was on track to hand in my thesis in a few months’ time.

But then something happened that threw me off course (well, erm, I threw myself off course).

I was asked by a company to run a series of workshops. Without even thinking, I said “Yes! I’d love to!”. It seemed like a great opportunity. One that was too good to pass up.

When I shared the news with my PhD supervisor, she seemed to think differently. Her face said it all: a mixture of concern and confusion.

“Why did you say yes to this? Do you need the money? What about your PhD? You’re so close to finishing”, she said.

The truth was I didn’t need the money. I said yes because without having my other commitments staring me in the face, I had all the time in the world. I was engaging in magical (delusional) thinking. I fantasised about having superhuman capabilities and being able to do it all.

I was wrong. There were only so many hours in the day, and something had to give.

To cut a long story short, pretty quickly the magical thinking wore off, and I regretted taking on the job. I had burdened my future self with a ridiculous amount of work and unnecessary stress.

But worst of all, I had delayed handing in my thesis by several months. A few months might not sound like much in the big scheme of things. But when you’ve been plugging away at a PhD for seven years, every month becomes precious. I risked losing momentum.

If I could teleport back in time and place a year-at-a-glance calendar in my office space, I like to think that I would have prioritised my PhD over the shiny new opportunity.

I recently finished reading an excellent book called ‘The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain’ by Annie Murphy-Paul.

In this book, Annie explores nine principles for expanding our intelligence (note: these principles are not taught in schools). She argues that instead of pushing our brains to work harder and harder, we can use our bodies, relationships, and surrounding environment to boost our cognitive abilities.

In the chapter called “Thinking with the Space of Ideas”, she writes:

“Whenever possible, we should offload information, externalize it, move it out of our heads and into the world. It relieves us of the burden of keeping a host of details “in the mind,” thereby freeing up mental resources for more demanding tasks like problem solving and idea generation.”

After reading this book, I understood why a year-at-a-glance calendar can be such a powerful tool. Seeing all your projects and commitments in one glance allows you to think smarter and more strategically.

These calendars also help to orient you in time. You can see how much time you have between now and doing the things you need to do.

Your projects and deadlines stare back at you every day. There’s no escaping them.

Seeing your life in this way also helps you to plan and pinpoint busy periods.

Here’s an example . . .

This month, I have more presentations scheduled than usual. This means I need to manage my energy levels, prioritise sleep, and eat healthily.

But a quick glance at my calendar tells me I have a few ‘free’ days before all these talks begin. I can use this time to cook a few meals to pop in the fridge and freezer to make life a little easier during this busier period.

One of the worst things I can do when I get busy is order takeaway food and sacrifice sleep to work. I refuse to do it as it always backfires. If I’m functioning at half capacity, my talks and work will suffer.

These calendars can also provide useful information to help you manage your energy levels, reduce ridiculous workloads, and avoid burnout.

Earlier this year, there was a week when I delivered more talks than usual. During this week, I found myself taking 15-minute power naps between talks to recharge before the next one. Even with all these power naps, by the end of the week, I felt tired. I drew a tired little emoji face on my calendar to represent this.

That tired emoji face is a constant reminder: you have mental and physical limits. Don’t overdo it.

It’s important to find a calendar that is both aesthetically pleasing and functional for you. This means you probably can’t just go to the shops and pick something off the shelf.

You could order a hard copy calendar online, but when the year is already well underway who wants to potentially wait weeks for their calendar to arrive in the mail?

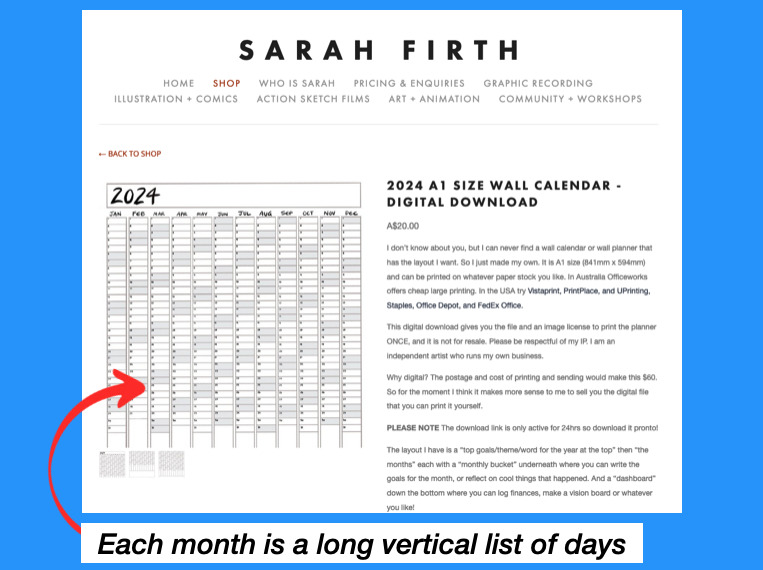

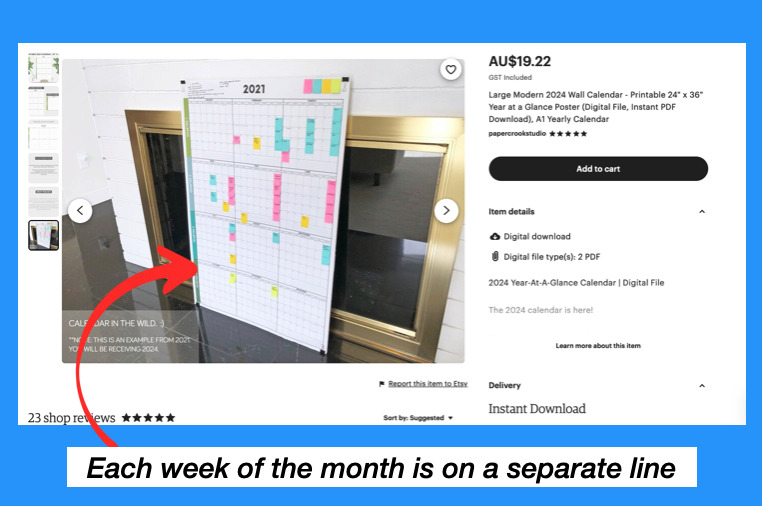

You can purchase a digital download online and take it to your local print shop on a USB stick. Some templates display the month as a long list of days; whereas other calendars group the month into weeks, with each week on a separate line (see examples below).

Alternatively, you could buy a monthly calendar, cut it up, and stick it together.

One of my friends suggested I try doing this. I gave it a shot, but my calendar looked like a failed arts and crafts project (with messy bits of tape plastered everywhere). Plus, the boxes were too small and cramped my style.

After some trial and error, I purchased a digital download from Etsy for $20AUD and printed it A0 size for $10AUD. All up, my calendar cost me $30AUD – money that was well spent.

The bottom line is you have to figure out what works for you and how much you’re willing to spend.

• Write on the calendar when all your exams, appointments, special events, and major projects will take place.

• If you don’t yet know the specific dates of each exam, note the week they begin and assume the worst-case scenario (your exams will be sooner rather than later).

• Consider laminating your calendar so you can use whiteboard markers on it.

• If laminating is too expensive, use sticky notes and washi tape instead.

• You can mount your calendar on core-flute material or foam board to give it a sturdier structure.

• Resist the urge to put every detail on your calendar. Focus on the big project deadlines, appointments, exams, etc. The details for what and when you work on each project can go into your weekly planner and/or on your to-do list.

• If you have the wall space, consider printing your calendar A0 size (841mm x 1189mm). You want plenty of space to write in each box.

In our noisy world where we are bombarded with endless opportunities, many of us would benefit from embracing analog tools like the year-at-a-glance calendar. These calendars help to ground us in reality and focus our minds on what matters.

If you have a lot going on in your world and find yourself saying “Yes!” to every shiny new opportunity that comes your way, do yourself a favour and create a year-at-a-glance calendar. Having your commitments stare you in the face every day is a simple but powerful way to live with greater focus and intentionality.

I recently watched a video of Gordan Ramsey cooking a ‘curry in a hurry’ (a butter chicken dish).

I was spellbound by the way Ramsey seamlessly cooked this dish. He was in flow and fully focused on the task of cooking the butter chicken.

What allowed him to whip up this dish plus a serving of rice in under 15 minutes?

Being organised helped a lot. Before he started cooking, chef Ramsey had all the ingredients and cooking utensils out on the bench, ready to go.

In chef’s speak, he had prepared the mise en place.

Mise en place is a culinary skill that can help us to study and work more efficiently. In this article, I explore this concept and how you can apply it to your life to help you stay calm, focused, and in control of your studies.

The mise en place is a French term that translates to “putting in place”. It means a place for everything and everything in its place.

Everything the chef needs is within arm’s reach. When it’s time to start cooking the dish, the chef knows where everything is. This allows the chef to focus on cooking the dish and stay calm and grounded under pressure.

In the book Kitchen Operations (a textbook for hospitality students and apprentice chefs), the authors write about the importance of being organised in the kitchen. They state:

“The ability to work in an organised manner is possibly the most important quality that anyone working in the preparation and service of food can demonstrate. You must develop this ability to complete the expected workload in the time available. Failure to be methodical in your approach will reduce efficiency and will lead to feelings of stress and frustration.”

The mise en place helps the chef avoid unnecessary stress and frustration.

Imagine the following scenario . . .

A chef starts cooking a pasta sauce.

The chef realises 10 minutes in that he is missing a key ingredient (tins of tomatoes).

The chef has to run to the shops to buy the tomatoes.

Chefs can’t afford to have that happen. They are time-pressured. They need to get meals out quickly to hungry customers.

The mise en place helps chefs avoid stressful situations like this. It can also help you decrease unnecessary stress, drama, and frustration associated with homework and study.

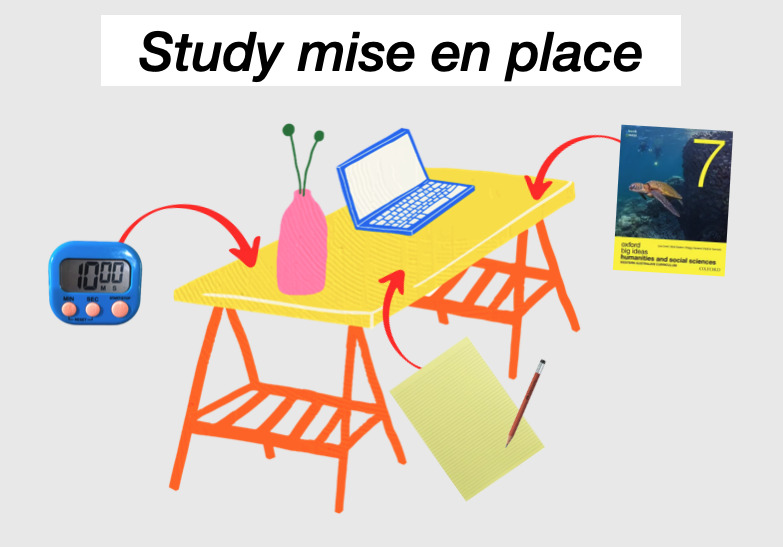

Before starting your work, set yourself up with everything you need to complete the task.

Think of this as the study desk mise en place. Ideally, you want to have a dedicated study space where everything is already set up. This saves you time, as you don’t have to set things up and pack things away after each study session.

But your desk isn’t the only space you can set up and prepare. In the world of study, you have other spaces you need to manage (e.g., a computer, school bag, pencil case, and locker). With each of these spaces, you need to ask:

“What items do I need in this space for my work to flow smoothly?”

It also helps to ask:

“What items don’t I want in this space?”

Just like a chef doesn’t want cockroaches, cats, and rats running around the kitchen and restaurant (or a visit from the local health inspector), there are things you want to keep out of your study space.

Remove anything that throws you off your game (i.e., makes you feel bad, distracted, overwhelmed, and upset) from your study space.

Here’s my list of things I want to keep out of my study space:

• My smartphone

• Long to-do lists

• Visual clutter

The point is to remove any friction points from your environment (anything that will slow you down and make it difficult to do your work).

The mental mise en place cannot be overlooked. This is the mental preparation part of the study process.

Ask yourself:

What must I do to mentally prepare myself for deep work/study?

Most of us can’t just scroll on our social media feed for an hour and launch straight into doing focused study. We need to get into the right headspace.

To be clear, I don’t mean you need to feel motivated, inspired, or in the right mood to study. Too often, we wait for motivation to strike, and it never comes. However, it certainly helps to be calm, focused, and grounded.

My mental preparation for the workday starts the evening before. Too many late nights have taught me that to wake up feeling calm and grounded, I need to go to bed at a reasonable hour.

When I wake up, I protect this mental calm by:

• Going for a walk or lifting heavy weights

• Doing a mini meditation (usually 3-5 minutes)

• Eating a healthy breakfast

• Avoiding checking my email and touching my computer first thing

• Journaling or mind mapping with pen and paper

I stay away from screens for as long as possible. This is essential for cultivating a calm mental state where I feel proactive and in control of my day.

I know I’m in trouble if I skip too many of the things on the list and start the day by checking my email. It becomes much more challenging to focus and get things done.

What is a pest of the mind?

It is anything that overstimulates the mind and leaves one feeling frenzied, scattered, and/or jangled.

Here’s the thing about learning information at a deep level: it requires you to slow down. You cannot rush it, like a 15-minute butter chicken dish.

But we engage with people, places, and things on a daily basis that speed up our thinking. In this overstimulated, wired mental state, learning feels like a hard slog.

Here’s a tip: start to notice the things that leave you feeling overstimulated. It can be incredibly liberating to cut back on these things or eliminate them completely from your life.

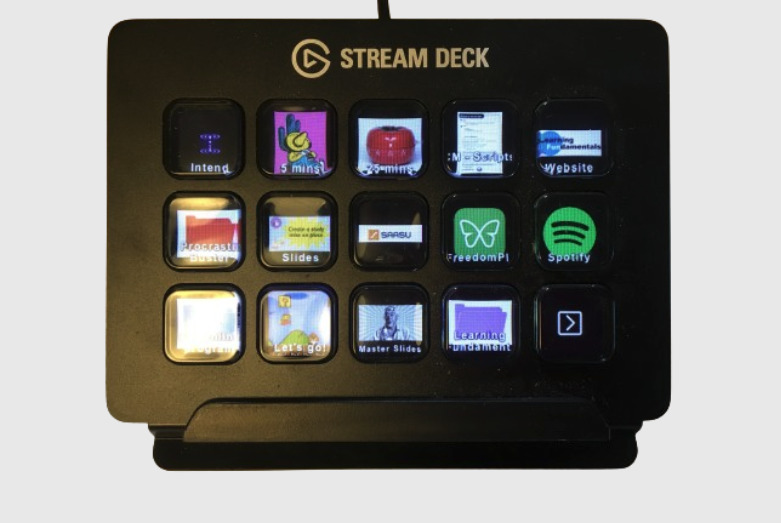

I am constantly tweaking my workspace and experimenting with different tools to help me click into a state of flow with my work. Here are some tools that I’m currently enjoying having as part of my study mise en place:

Technically, this is a gaming device that allows gamers who stream to switch scenes, adjust audio, etc at the tap of a button. I’m not a gamer, but I use my Stream deck to get started with various tasks and projects I feel resistance towards.

Instead of thinking, “Where is this file located? How do I get to it?” I tap a button on the Stream deck and it opens the file up. I tap another button, and it opens an application I frequently use.

No more frustrating clicking through numerous folders trying to find the document I need! The Stream deck helps to remove a big mental barrier and kick-start the work process with ease.

Stream decks aren’t cheap but if you can find one secondhand or on special like I did, they are well worth it.

Staying hydrated is super important. I fill a big jug with water every morning and place it on my desk with a glass. If water is within arm’s reach and I can see it, I find myself taking regular sips throughout the day.

I used nasty, cheap pens for years. Being a sucker for free stuff, I collected free pens at career expos and university open days. Without even realising it, these pens caused me a great deal of frustration and irritation.

These days, when it comes to pens, I don’t mess around with junk. There’s one pen I love using: the uniball signo (0.7). It’s a gel pen (you can find them at Officeworks). Writing with this pen is an absolute pleasure.

As Kevin Kelly says:

“Take note if you find yourself wondering “Where is my good knife?” or “Where is my good pen?” That means you have bad ones. Get rid of those.”

It’s super handy to have a notepad to jot down ideas and random thoughts as they arise. I recently discovered Rhodia notepads (a recommendation by The Pen Addict, Brad Dowdy). Writing on this paper feels like writing on butter!

Whenever I notice I’m procrastinating, I’ll set my timer for 10 minutes and say, “All I need to do is 10 minutes on this task. That’s all. Just 10 minutes”. I set the timer and away I go.

Other times, when my workspace looks like a mess, I’ll set a timer for 3 minutes and spend that time getting things back in order.

My planner tells me what to do and when to do it. For the last 6 weeks, I have been experimenting with Cal Newport’s time blocking method (planning my day in hourly blocks). It sounds torturous, but it’s strangely liberating.

When I open my planner, I can see what is happening for the week, but I don’t have a sense of the bigger picture. This is why I printed out a massive (A0 size) year-in-a-glance planner to schedule all my presentations, holiday breaks, special events, etc.

Having this calendar makes me feel more in control of my life. I can see when I have busy periods of presenting and when I need to balance those periods with extra rest time to sustain myself. I can also see events and deadlines relatively to where I am now.

These are just a few things I love having in my study/work mise en place. But we’re all different, so you need to figure out what works best for you.

When I recently asked a group of high school students what items they would need in their study mise en place, here’s what they came up with:

• Snacks

• Phone

• Pencil case

• Squishmallows

The first three suggestions didn’t surprise me, but the squishmallows sure did (the students were shocked that I’d never heard of a squishmallow before). I had to google them (they are soft toys).

But I get it.

A squishmallow is fun.

It’s comforting.

It makes you feel good.

If something makes you feel good, go put it on your desk. Because if you feel good, it will be easier to think and learn.

The mise en place is a skill that can help all of us (not just chefs) focus on the task at hand. The point is you need to make your study mise en place work for you. You need to find the combination of ingredients that hits the spot.

Like a top chef has their favourite chopping knife, you’ll have your favourite pen. Spend some time experimenting with various tools and different work setups. By creating a more streamlined and organised study space, you’ll get that time back. Plus, you’ll find it’s much easier to get going and keep going with your work.

Where I live in Perth Western Australia, there’s an event that happens once a year that demands your attention like no other: The Royal Show.

At this show, there are extreme rides, giant fluffy toys to be won, baby animals you can pat, and much, much more.

Wherever you are in the world, you probably have an event like this, too. And if you do, chances are there is something at the show that is completely attention grabbing . . .

I’ve come to see show bags as being an important metaphor for modern life. Let me explain . . .

When I was a child, I couldn’t wait for the show bag catalogue to be released. I would spend hours trawling through the catalogue, carefully selecting my show bags.

These were big and important questions for my 6-year old brain.

When we finally got to the show, my parents and I would wait in the queue at the frenzied show bag stall. I remember looking up at the display of all the bright colourful show bags and feeling really excited.

If you break down the contents of a show bag, there’s a bit of a formula to them . . .

There’s usually a range of ultra-processed sugary and salty snack foods and a bunch of novelty toys.

If you take a good hard look at the contents of most show bags, there’s nothing that’s really nourishing in there. It’s just poor-quality junk food. Or cheap plastic rubbish that is destined for landfill.

As I got older, I wised-up to these overpriced show bags containing mostly garbage. I stopped buying them.

Now you’re probably wondering, “What do show bags have to do with being able to study effectively? How is this a metaphor for modern life?”

I’ve come to see show bags and the Royal Show as being similar to smartphones, specifically social media apps.

If consumed frequently (even just in small doses), they are potentially damaging to our minds, bodies, and the planet.

Think of it like this . . .

But if you were to have a show bag every day, would you enjoy it as much?

Probably not.

According to addictions expert Dr Anna Lembke, if you consume too much of a pleasurable thing, it makes that thing less pleasurable.

This is why they say, “Less is more”.

There’s a reason the royal show only happens once a year and you can’t buy show bags at the local supermarket. It’s a special occasion. Show bags are designed to be a special treat.

It wouldn’t be so special if it happened all the time. After a while, the novelty would wear off. You’d get bored.

As you emptied the contents of your 50th Bertie Beetle show bag or entered the Gravitron for the 100th time, you’d be like “Meh. Big deal”.

If you don’t believe me, next time you’re at the show take a look at the carnies (the carnival workers). They’re not having fun in sideshow alley. They’re tired. They want to be packing up the rides and getting out of there.

The point is the Royal show and show bags are great once in a while but not all the time.

It’s the same deal with social media. Spending too much time on there isn’t doing you any good.

Switching rapidly from doing your work to your phone and then back again slows you down. It impairs your ability to think and learn. It makes you feel scattered and anxious, too.

It’s time to start thinking of TikTok, YouTube videos and text notifications as the sugary treats, salty snacks, and novelty toys contained in show bags. Nice to have occasionally, but if consumed in large quantities, you’re going to suffer.

Just because everyone is eating Bertie Beetles all day every day doesn’t make it healthy. It doesn’t make this behaviour okay. It just means we’re going to end up with a very sick society.

We can do better. But this means we need to place limits on how much we consume.

When you study with your phone within arm’s reach that’s like having a never-ending show bag of junk food next to you. You can’t fully focus your mind on the task at hand because a part of your brain is thinking about the tasty treats in the bag.

No matter how hard you try not to think about the treats, you can’t help but think about the treats!

It’s not your fault that you can’t resist checking your phone for the treats that await you. Social media apps are designed to be dopamine dispensing machines. Addictive to the core.

How can you fill up on the good stuff (i.e. the stuff that is going to add real value to your life)?

I recently developed a powerful tiny habit. It may sound simple but I highly recommend it. The habit is this . . .

When I notice my phone is in my workspace, I will pick it up and put it away from my body in another room.

In fact, I have a specific home for my phone: it lives in pocket number 1 of a vertical wall hanger in my dining room. I have set times when I can check my phone. But outside those times, my phone stays in pocket 1.

When I put my phone in the pocket, it’s like I’m putting the show bag away on the top shelf of a cupboard and closing the cupboard door. Out of sight is out of mind.

I recommend you give it a shot.

When you first start implementing this habit, you will probably feel a strong urge to grab your phone and look at it. But over time the urge to check your phone will pass.

The thing about focus is it’s like a muscle. You can strengthen it over time by engaging in simple practices, such as putting your phone away when it’s time to do your work and engaging in meditation.

Doing these things may be more difficult than dipping into a show bag or watching TikTok videos, but it’s probably going to deliver far more benefits in the long run.

But most importantly, when you fully focus your mind on what you need to do, there is something inherently satisfying about that. It brings you more joy and satisfaction than any 15 second video could ever deliver.

Image Credit

“Ekka 2004 Showbag Pavillion” by Dr Stephen Dann is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive sessions on learning to learn, combating procrastination, exam preparation, how to focus in the age of distraction, habit formation and much, much more!

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to our newsletter:

© 2024 Learning Fundamentals