I recently took an online test to figure out what my learning style was. According to learning style theory, we all have a preferred bodily sense through which we learn information best. Some of us are visual learners, others auditory learners, and the rest of us kinaesthetic learners.

Based on the learning style concept, if you want to succeed at school then you should learn information according to your preferred learning style.

After years of teaching study skills, I thought it was probably time to take a learning style test. So I jumped online, found a test, and answered a long list of multiple-choice questions. And then I clicked submit, feeling quietly confident that the result would be ‘visual learner’.

But it wasn’t. I came up as a kinaesthetic learner.

“There must be some mistake with the algorithms”, I thought as I clicked the refresh button. But there was no mistake. Kinaesthetic learner it was.

This result threw me into mental turmoil. Let me explain why…

I’m a doodler. Ever since my first year of university, I’ve been pumping out drawings to capture information at lectures and workshops. If it wasn’t for thousands of crazy little pictures on hundreds of mind maps, I wouldn’t have completed degrees in Law and Psychology and a PhD.

I also love it when concepts are explained in comic style format. My brain screams, “Yes! I get this! This makes sense”.

So why in the world was this online test telling me that I learn best through doing? What was with that?

Did this mean mind mapping wasn’t for me? Did it mean it was time to lay my coloured pens to rest? Was it time to kick the explanatory comics to the kerb?

This got me thinking about learning styles. Was there anything to them? Any empirical research to support them?

So I started looking into learning styles with the help of Google Scholar. And here’s what I discovered…

Learning styles are an educational myth

I get it. It’s hard to swallow because we hear about learning styles all the time. Perhaps a teacher you respect and admire taught you about them. Maybe you had to fill in a questionnaire at school about your preferred learning style. There are entire conferences and hundreds of books dedicated to the topic.

But when information is so widespread like this we start to actually believe it

We start to think, “Oh, there must be something to this. Why would so many books be published on it otherwise?”. We start to collect evidence for how we are auditory or visual learners, which makes us believe in our preferred learning style even more.

But in actual fact, learning styles are a bit of a limp lettuce leaf when you look at the research. There is no evidence that changing the mode of presentation to suit a student’s learning style helps the student to learn better.

No one is disputing the fact that we all learn differently

We have different interests and different background knowledge. Understanding these kinds of differences when it comes to learning is critical. But it’s this whole business of figuring out our preferred bodily sense through which we take in information where we’ve lost our way.

Riener and Willingham put it like this:

“If I were to tell you “I want to teach you something. Would you rather learn it by seeing a slideshow, reading it as a text, hearing it as a podcast, or enacting it in a series of movements,” do you think you could answer without first asking what you were to learn – a dance, a piece of music, or an equation? While it may seem like a silly example, the claim of the learning styles approach is that one could make such a choice and improve one’s learning through that choice, regardless of the content”

Plus, let’s not forget that learning is a complex task. As Psychologist Phil Newton says:

“Think of learning about, well, anything – playing the guitar for example. You can’t do that without picking it up and playing it (Kinaesthetic), listening to your efforts as you do (Auditory), reading instructions about what to do (Reading) and looking at images of finger positions for chords and notes for the music (Visual) – the meaning of what is being learned is so much more complex than one or two of these four modalities.”

Simply put, you learn in multiple ways. So don’t limit yourself with a learning style label.

No learning styles? No problem!

Here’s what I recommend teachers and students focus their time and energy on instead of learning styles.

For students:

If you want to learn more effectively, you’re better off using effective study techniques, which have scientific backing. Strategies such as practice testing, taking effective notes, and explaining concepts to another person. These strategies have all been shown to help students retain information effectively.

For teachers:

Instead of asking, “Does the format of the content match the student’s preferred learning style?” think about the nature of the content you’re going to deliver. Regardless of whether it’s a video or a podcast, ask these questions:

Is this material going to be engaging and interesting for students?

Is this material suitable given the student’s level of knowledge?

In short, go for study strategies and engaging, relevant content (not learning styles).

Share This:

I don’t think so.

Students who look like they are naturally smart just have a bit of a head start on the rest of the class.

From the outside, it looks like easy street for these ‘smart’ students. They are cruising along, getting good marks without a lot of effort (or so it seems). But because we are not privy to every aspect of their lives, most of us are completely unaware of the invisible advantages these students have.

Invisible advantages?

Let me explain . . .

I know a young man who did really well at physics in high school. From the outside, it looked like he was naturally talented at the subject. But if you were to take a closer look at his home environment, you’d soon realise that there were other factors at play.

Guess what his parents do for a living?

They are both award winning physics professors.

From a very young age, he got to travel the world with his parents as they attended physics conferences.

Guess what his older brother does?

He’s an academic, too. In which department?

Physics.

Think about it, since the day he was born he has been immersed in the world of physics. His family lives and breathes physics!

When family friends (i.e. other physics professors, PhD and Masters students) come over for dinner parties, what do you think they talk about?

Physics.

You’d expect this young man to excel at physics!

But not because he’s naturally smart at it (he’s not). He excels because he’s been exposed to the ideas and language much more than the average physics student. And in year 12, if he got stuck? Plenty of help was at hand. It was like he was living with three private physics tutors.

Of course, I have to give this young man some credit. His success didn’t solely come down to his family members being physicists.

He applied himself.

He turned up to his physics classes.

He studied for his tests and exams (his parents and brother couldn’t do this work for him).

But it helped being raised in an environment where physics was seen to be fun, exciting and fascinating. It helped a lot.

In his book Atomic Habits, James Clear tells the story of a Hungarian man called Laszlo Polgar and his three daughters, Susan, Sofia and Judit. He states:

“Laszlo was a firm believer in hard work . . . he completely rejected the idea of innate talent. He claimed that with deliberate practice and the development of good habits, a child could become a genius in any field. His mantra was “A genius is not born, but is educated and trained.”

Laszlo wanted to test out this idea with his three girls. So here’s what Laszlo did . . .

“Laszlo decided chess would be a suitable field for the experiment and he laid out a plan to raise his children to become chess prodigies. The kids would be home-schooled . . . The house would be filled with chess books and pictures of famous chess players. The children would play against each other constantly and compete in the best tournaments they could find. The family would keep a meticulous file system of the tournament history of every competitor the children faced. Their lives would be dedicated to chess.”

You bet!

Here’s how James Clear sums up Laszlos’s daughters’ achievements:

“Susan, the oldest, began playing chess when she was four years old. Within six months, she was defeating adults.

Sofia, the middle child, did even better. By fourteen, she was a world champion, and a few years later, she became a grandmaster.

Judit, the youngest, was the best of all. By age five, she could beat her father. At twelve, she was the youngest player ever listed among the top one hundred chess players in the world . . . For twenty-seven years, she was the number-one-ranked female chess player in the world.”

Now you might be thinking, “What kind of gruelling childhood did these poor girls have?” but don’t feel sorry for them. If you watch interviews (like this one), you’ll hear the sisters talk about how enjoyable their upbringing was. They really loved playing chess.

Your parents don’t need to be world experts for you to excel at school and life. The point is this . . .

You can improve in any area if you apply yourself.

But you’ll need to develop an interest in your subjects. Don’t rely on your school teachers to make your subjects interesting. It’s time to take charge of your learning. It’s up to you to find ways to make learning fun.

Don’t limit yourself to your textbook. Go and explore other resources: online courses (check out classcentral.com), TED talks, interesting podcasts, documentaries, free talks and your local library.

Read as much as you can. Ease into new topics with graphic novels and kids books. Once you’ve mastered the basics, move onto more complex reading materials.

Finally, if you can, surround yourself with people who have similar goals and interests. They may not be in your neighbourhood or school community, but you can find them in online communities.

For example, I was interested in learning more about how to eat and cook in a healthy way. So I enrolled in an online course that explored plant-based nutrition. This course connected me with people from all over the world who were also interested in developing healthy eating habits.

Instead of feeling like I was being a bit extreme for saying no to the Frankfurt sausages and party pies at events, this online community empowered me to keep making healthy lifestyle choices.

As James Clear says:

“One of the most effective things you can do to build better habits is to join a culture where your desired behaviour is the normal behaviour. New habits seem achievable when you see others doing them every day. If you are surrounded by fit people, you’re more likely to consider working out to be a common habit. If you’re surrounded by jazz lovers, you’re more likely to believe it’s reasonable to play jazz every day. Your culture sets your expectation for what is “normal”. Surround yourself with people who have the habits you want to have yourself. You’ll rise together.”

1. What do you want to learn and/or get better at?; and

2. Are there any communities that can support you with this?

Whatever you want to learn or do, approach it with an adventurous spirit and bring a few people along for the ride. It’s much more fun (and effective) when you learn and grow together.

• Highlight or underline your books?

• Test yourself with flash cards?

• Create notes?

• Make an outline of the key topics?

• Reread your books and/or notes?

These are all popular study strategies and exam revision techniques. But how effective are they? And could you do them better?

In their paper, cognitive psychology researchers Miyatsu et al (2018) examined how students can optimise the use of the following five study strategies:

1. Note-taking

2. Rereading

3. Marking (Underlining or highlighting)

4. Outlining

5. Flash cards

Do you have a tendency to write down word for word what the teacher says?

It’s best to summarise or paraphrase the information. Put it in your own words.

Do you prefer to take notes with pen and paper or on a laptop?

Taking notes by hand is best.

Why? Because you can’t write as fast as the teacher speaks, so you’re more likely to capture the information in your own words.

But when students take notes on a laptop they usually can type as fast as the teacher speaks. So what happens is you get a word for word script of what the teacher said. The problem is you don’t remember as much of the information when you take notes this way.

But regardless of whether you take notes by hand or on a laptop …

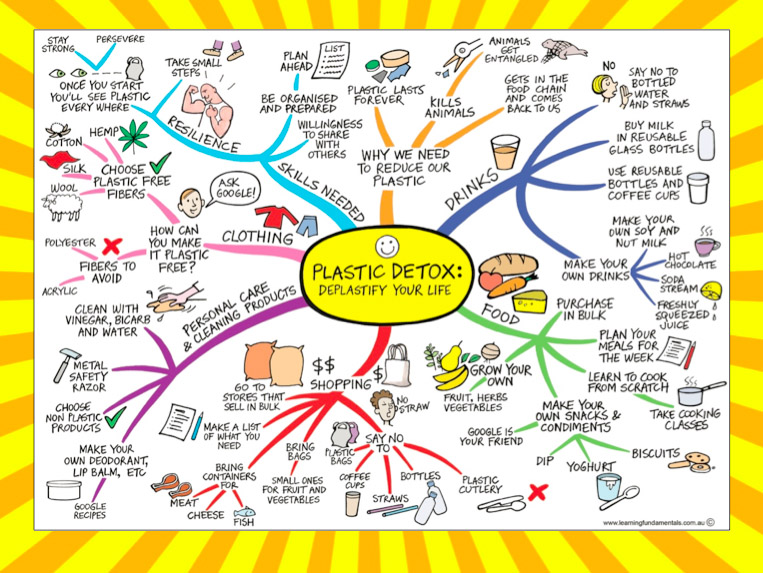

Don’t let your notes just sit there. Work with them. Transform them into pictures and flash cards. Scribble questions and other ideas all over them.

If I need to commit information to memory, I always do one or more of the following:

• Mind map out my linear style notes

• Put key points onto flash cards

• Transform them into practice tests

Miyatsu et al (2018) state:

“Reviewing is crucial in reaping the full benefits of note-taking.”

Remember, your notes are pretty much useless unless you review them.

I’m not a fan of reading passively.

If I’m reading complex information, I block out distractions (e.g. turn off music and put my phone in another room) and I draw pictures as I read. When I read this way, there’s usually no need to reread.

But if you reread passively (e.g. no drawing), try doing the following to make the ideas stick:

Space out the first and second reading by a few days. Research shows this produces more durable learning.

Before rereading, try doing retrieval practice. Retrieval practice is when you force yourself to bring information to mind (without looking at your books and notes).

Retrieval practice has been identified it as the number one study strategy. Use retrieval practice and you’ll dominate your subject areas.

1. Use a blank piece or paper or a whiteboard to write down all the things you can remember on the topic.

2. Try explaining to a friend, the wall or a pet what you can remember on the topic.

3. Use flash cards to test yourself.

Tip: It’s okay to retrieve the wrong information, just as long as you correct yourself.

So make sure you check to see that you are retrieving the correct information. It’s critical!

This isn’t a good study strategy to use. It gives you a false sense of confidence. You think the information has transferred from the page into your brain, but usually it hasn’t.

But if you really must highlight, you need to exercise some serious restraint with yours pens.

Read a section of the text first to get a sense of the important ideas (no pens allowed). Only after you have read the section are you allowed to underline the key ideas.

Personally, I think it’s more effective to draw pictures in the margins or on a blank sheet of paper as you read.

Please don’t make highlighting or underlining your only study strategy. As the Miyatsu et al (2018) state:

“Marking should not be students’ only preparation method for higher-order assessments.”

You know how your books have a contents page? Outlining is where you create a contents page for a subject.

Do you have a syllabus or unit outline for each of your subjects? If you do, check the unit content section. Boom! That’s your outline.

Don’t have an outline? Create one for a subject/topic. This will give you a sense of the key ideas and how they are structured.

Here’s another way you can do retrieval practice using an outline …

Use your outline to test yourself.

Go through each topic and see how much you can remember (“What do I know about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs?”).

Get easily overwhelmed by a long list of topics? No problem!

Simply use a blank piece of paper to cover up the topics. Then proceed through the topics, one by one, shifting the paper down the page as you successfully bring to mind information on each point.

If you use flash cards correctly, this is a great way to do retrieval practice.

Use your flash cards to test yourself.

But here’s the thing: don’t just read the question and then flip and read the answer straight away. Try bringing the information to mind before you flip the card over.

It’s tempting to want to drop a card when you get the answer correct (“I know that!”). But hold onto that card. Keep it in your pile of flash cards. Only drop a card after you have successfully retrieved the correct information at least three times. Remember, the aim is to strengthen the information in your mind so you can easily recall it later on.

While you’re at it, space out your practice. Go through a pile of flash cards and then take a break before practicing them again (my recommendation is to wait at least 24 hours).

Continuously drilling your flash cards is not an effective way to study.

After completing a set of flash cards, go outside and get some fresh air, make yourself a smoothie, etc. Do something good for yourself. Your brain deserves a break.

Note: For learning more complex information, flash cards may not be the best strategy to use. I prefer drawing the information out first and then creating flash cards for key concepts on the mind map.

So there you have it! Various ways to optimise five popular study strategies.

Just remember, if you want to save time and elevate your studies, you are better off using strategies that have been found to be highly effective (click here to read more about highly effective study strategies).

But if you’re in the habit of using the popular strategies mentioned above, that’s okay! Why not make some small tweaks and try adding some more effective strategies into your study routine?

While they may not feel as good and easy as highlighting, they will certainly fast track your studies and boost your performance.

If you want to achieve solid marks at school, you need to be strategic. Ditch your highlighter pens. Stop re-reading your books and notes. These are incredibly boring and passive ways to study. You need new study strategies.

Dual coding is when you use both words and pictures to learn information. This gives you two ways to learn the information (via the words and the pictures).

Here are some different ways you can dual code when you study:

Is the picture conveying something that the text isn’t?

Think this strategy is only for visual learners and artistic types? Think again. Dual coding has nothing to do with learning styles and being a visual learner, which some people argue is an educational myth. Dual coding is for everyone.

Without looking at your books and notes, try to recall the information. Ask yourself, What did I study in human biology yesterday? Force yourself to get the information out of your brain.

The simple act of bringing information to mind helps to reinforce it in your brain.

You see, it takes effort to transfer information into your long-term memory. You don’t just hear information once in class and … BOOM! That information stays in your brain forever. Sorry, it doesn’t work like that.

We are incredibly forgetful so we need to revisit the information to help cement it in our brains. Retrieval practice is the best way to do this.

Let me make one thing clear: Retrieval practice is not the same thing as repetition.

Repetition is easy (you just read the information over and over again). But retrieval (forcing yourself to bring specific information to mind) is hard. It strains your brain. But it’s a good kind of muscular strain.

Just like it’s good to push your body at the gym, retrieval practice is the ultimate workout for your brain. It will help shift information into your long-term memory so you can access it when you need it.

Here are some different ways you can practice retrieval:

When you get to the point where you can’t recall anything else, that’s when it’s okay to take out your books and your notes. Check for any mistakes and gaps in your knowledge.

As Dr Barbara Oakley says:

“Getting clear on what you don’t understand is 80% of the battle.”

It’s also important to know that you’re retrieving the correct information (otherwise, you’ll be reinforcing the wrong stuff!).

If you’re consistent with your retrieval practice and incorporate it into your study sessions, you’ll see dramatic improvements over time.

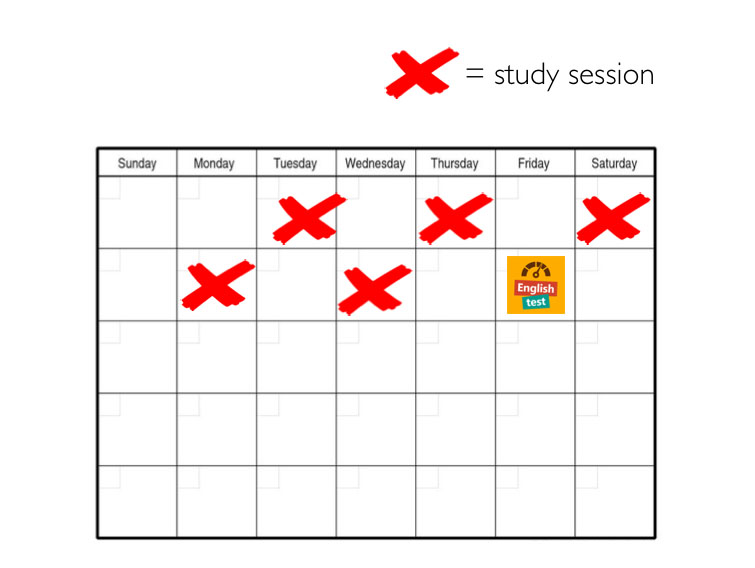

Rather than doing 5 hours of study right before your exam (i.e. cramming), it’s much more effective to space out those 5 hours of study over 2 weeks. You learn more by spacing out your study.

Now if you’re used to the cramming approach, spreading out your study over 2 weeks will probably feel strange at first. It will require a little planning. But the more you do this, the easier it gets. Before you know it, it will become a habit.

When you sit down to do spaced practice, keep in mind you only need to do 15-20 minutes of study before taking a break (not hours and hours of study).

The spaced practice approach usually means you’ll:

Why? Because you won’t need to stay up late or pull an all-nighter to study for your test or exam.

Have you ever spent time with a 4-year-old child? If so, you’ll notice they ask Why? a lot. It’s this natural curiosity that makes 4-year-olds like sponges, soaking up information from absolutely everywhere.

When you sit down to read your textbook, you want to ask Why? and How?

Ask questions such as:

Asking questions will help you to stay engaged with the material.

For some subjects (e.g. economics and psychology) you’ll need to learn lots of definitions of abstract ideas and concepts. If you’re like most students, you probably memorise these definitions by repeating them over and over again.

But if you do this, two things are likely to happen:

1) You’ll probably feel like a robot; and

2) You won’t fully understand the concept, which will make it hard to remember.

We can get ideas on how to learn definitions more effectively by looking at how professional actors learn their lines. Professional actors don’t learn their lines word for word. Instead they try to understand the character’s motivations and needs. Gaining a deeper understanding of these factors helps the actor to learn their lines more efficiently.

Similarly, gaining a deeper understanding of an abstract concept will help you to learn and memorise it. So the question is, what is going to help you to deeply understand the abstract concept?

Good examples. And lots of them.

Whenever you have to memorise an abstract concept, collect as many different examples as possible. Get examples from your teachers, from your textbooks, etc. Plaster those examples over your wall and in key locations in your house (e.g. on the mirror and fridge).

a) Ideas

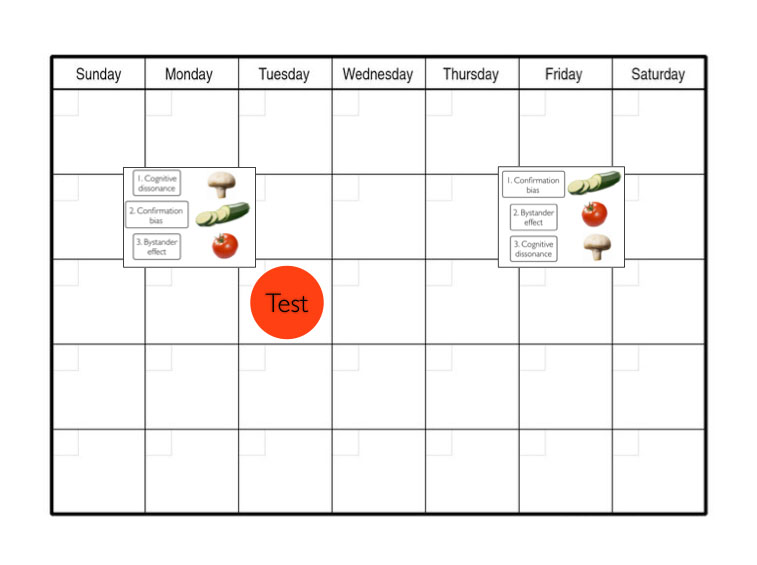

If you were going to a barbeque, you wouldn’t bring along veggie kebabs that only contained zucchini on the skewer. That would look cheap and nasty! One of the joys of kebabs is the variety of vegetables (e.g. tomato, onion, zucchini, capsicum). So you’d want to mix things up to make the kebabs appetising.

The same thing applies with your studies. Don’t just study one concept for a long period of time. Mix things up. Study one idea and then jump to another concept in the same subject.

For extra bonus points, you could pretend to be 4-years-old and ask yourself, How are these two ideas similar? and How are they different?

b) Location

Don’t always study in the same place. Sometimes study in a quiet café, a library or at the kitchen table. Research has found that changing your surrounding environment slows down forgetting and enriches learning.

7. Take notes by hand

Want to remember more information? Ditch your laptop and work with pen and paper.

A study called The pen is mightier than the keyboard found that students retained more information when they took notes by hand than when they took typed notes on their laptops.

When you take notes on your laptop, you tend to write word for word what the teacher is saying. This is because you can type at the same speed the teacher is speaking at.

But when you take notes by hand, you can’t write as fast as the teacher speaks. This forces you to put the information in your own words. This makes it easier for you to understand the information, which explains why you tend to remember more of it.

Why is it that some people with dementia can’t remember the names of their friends and family, but they can remember the lyrics to hundreds of songs?

It’s because music touches many different regions and lobes of the brain, which helps to cement the lyrics into our brains.

This makes music an incredibly powerful learning tool. Certain types of music can motivate you to study and complete tasks that you typically perceive painful and would prefer to avoid doing.

But more importantly, music can also help you to learn important concepts.

Jump on YouTube and you’ll find a range of educational songs (check out the circulatory song Pump it up! and this quadratic formula song. You can even learn how to make a lasagna with music.

Here are some ideas on how you can use music to help you study:

Have some fun and use humour wherever possible.

Working on a difficult problem? Feeling stuck? Then take a break. Allow your brain to go into what Dr Barbara Oakley calls the ‘diffuse mode’ of thinking.

In the diffuse mode, you relax your attention and allow your mind to wander. Let your subconscious mind do the work for you.

You often hear stories of famous scholars coming up with groundbreaking theories while relaxing under an apple tree, going for a walk or having a shower. In these diffuse mode states, their brains are still working away on the problem, which ultimately leads to these ‘Eureka!’ moments.

Some activities that will help you to enter the diffuse mode of thinking are:

It may seem like you’re wasting time in the diffuse mode but you’re not. Your brain is still working quietly in the background on the problem, even though you’re not actively focusing on it.

Okay, so this isn’t exactly a specific study strategy but it’s critical to all of the strategies listed above. You see, when you sleep, your brain doesn’t just turn off. The opposite actually occurs. Your brain gets busy doing the following:

This is why going over important information before you take a 90-minute nap or go to sleep at night can be beneficial for learning. Your brain is more likely to rehearse this information and strengthen it while you sleep.

Most importantly, it’s critical that you get a solid 8-10 hours of quality (undisturbed) sleep each night. If you’re sleep deprived, these effective study strategies cease to be effective.

Getting sufficient sleep will ensure that you can concentrate and recall information more easily in your tests and exams. So if it’s approaching midnight and you’re thinking, Maybe I can squeeze in another hour of study … think again. Always prioritise sleep over study. Your brain will thank you for it the next day.

To get maximum benefit from these ten study strategies, you need to be able to focus when you use them. Why? Because distraction is the enemy when it comes to learning information. If you’re trying to study complex information while checking your phone and watching a Netflix series, you’re wasting your time.

So before you sit down to study, deal with any potential distractions. Do this …

Turn your phone off. Place it in another room far, far away. Close your bedroom door so you can’t be disturbed.

The aim of the game is to form effective study habits. This isn’t hard to do and it’s never too late to give it a shot. It just takes practice, perseverance and being willing to try something new.

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive sessions on learning to learn, combating procrastination, exam preparation, how to focus in the age of distraction, habit formation and much, much more!

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to our newsletter:

© 2024 Learning Fundamentals