Most of us do. We sit and stare at our screens or textbooks for large chunks of the day.

You’ve probably heard the phrase, “Sitting is the new smoking”. It sounds dramatic, but sitting for 30 minutes or more leads to:

• Reduced blood flow to the brain

• Increased blood pressure

• Increased blood sugar

• Reduced positive emotions

Even if you exercise at the gym, if you sit all day at work or school, that’s not good for you.

Most of us know we should move more and sit less, but knowledge doesn’t always translate into action.

I’ve known for years about the harms of sitting. Every year, I’d set a goal “To move more during the day”. But it wasn’t until this year that I finally got off my butt and started taking regular movement breaks. In this blog, I’ll share what made all the difference.

Part of my problem was telling myself to “move more” and “sit less”. This was way too vague for my brain.

When it comes to taking movement breaks, how long should we move for? How frequently? And at what intensity?

I recently came across a brilliant study, published in 2023, that answered some of these questions.

A team of researchers at Columbia University compared different doses of movement on several health measures (e.g., blood sugar, blood pressure, mood, cognitive performance, and energy levels).

The researchers were interested in exploring how often and for how long we need movement breaks to offset some of the harms of sitting for long periods.

So, what did they do in this study?

Researchers brought participants into the lab and made them sit in an ergonomic chair for 8 hours. Participants could only get up to take a movement break or go to the toilet.

They tested five conditions:

• Uninterrupted sedentary (control) condition (Note: no movement breaks)

• Light-intensity walking every 30 minutes for 1 minute

• Light-intensity walking every 30 minutes for 5 minutes

• Light-intensity walking every 60 minutes for 1 minute

• Light-intensity walking every 30 minutes for 5 minutes

The optimal amount of movement was five minutes every 30 minutes. This movement dose significantly reduced participants’ blood sugar and blood pressure and improved their mood and energy levels.

That said, even a low dose of movement (one minute of movement every 30 minutes) was found to be beneficial.

Although walking has been described as ‘gymnastics for the mind’ and numerous studies show brisk walking can improve cognitive performance, they found no significant improvements in participants’ cognitive performance in this particular study.

You can read the full study here.

When it comes to any research conducted in the lab, the question worth asking is: Is it possible for people to do this in the real world? And if so, will they experience similar benefits?

Journalist Manoush Zomorodi wanted to find out. So, she teamed up with Columbia University researchers to explore whether people could incorporate regular five-minute movement breaks into their day.

They created a two-week challenge where people could sign up to one of three groups:

1) Five-minute movement breaks every 30 minutes

2) Five-minute movement breaks every hour

3) Five-minute movement breaks every two hours

Over 23,000 people signed up to participate in the challenge. Sixty per cent completed the challenge.

What did they find?

Five-minute movement breaks improved people’s lives, whether taken every half hour, hour, or two hours. They felt less tired and experienced more positive emotions.

They found a dose-response relationship. This meant that the more frequently people moved, the more benefits they gained.

In the Body Electric podcast, Columbia University researcher Dr Keith Diaz said a preliminary analysis of the data showed:

• People who moved every 30 minutes improved their fatigue levels by 30%.

• People who moved every hour improved their fatigue levels by 25%.

• People who moved every 2 hours improved their fatigue levels by 20%.

Here’s the thing, though . . .

Dr Diaz pointed out that most people weren’t getting all their exercise breaks in. On average, they took eight movement breaks each day (note: the researchers recommended 16 movement breaks a day), but they still experienced benefits.

Here’s what I take from all of this . . .

You don’t have to do this perfectly. There are no hard and fast rules. Doing some movement is better than doing no movement.

All movement matters. It all adds up.

Although movement is natural and good for the mind and body, my brain often resists the thought of getting up and moving (“No! I don’t want to get out of this cosy chair!”).

What’s up with that?

In the book Move the Body, Heal the Mind, Dr Jennifer Heisz explains that our brains hate exercise for two reasons:

1) The brain doesn’t want to expend energy; and

2) Exercise can be stressful.

This has to do with how our brains are wired and our deep evolutionary programming.

If we go back in time, our hunter-gatherer ancestors had to be constantly on the move to gather food, build shelter and run from hungry animals. All of this activity required a lot of energy. Since food was scarce and energy was limited, hunter-gatherers had to conserve their energy.

If you were to offer a hunter-gatherer a free meal and a comfortable place to stay, would they take it? You bet they would.

The problem is our brains haven’t changed in thousands of years. We still have the same brain wiring as our ancient ancestors.

This is why my brain often throws a tantrum and comes up with all sorts of excuses to avoid my morning workout.

In this modern world, with all the calorie-dense fast food, comfy chairs, and modern conveniences, our brains get confused.

As evolutionary psychologist Dr Doug Lisle, author of The Pleasure Trap, states, in the modern world:

“What feels right is wrong. And what feels wrong is right.”

Understanding that we operate with an ancient brain that isn’t suited to this modern world opens up new possibilities. For example, you can use your prefrontal cortex (the rational part of your brain) to override the primitive instinct to stay comfortable.

Here are some strategies I’ve been experimenting with to get me taking regular five-minute movement breaks:

I’ve strategically placed electronic timers in every room I spend a lot of time in (e.g., my office, outdoor desk, and dining room). Before I sit down to start a task, I set a timer for 25 minutes.

When the timer goes off, that cues my brain to get up and move.

When the timer goes off, I usually jump on my treadmill for a five-minute walk. But not always.

Whenever I feel like doing something different, I play a little game with myself.

The game is simple:

I roll a dice with different movement activities I wrote on each side. Whatever activity it lands on, I do it.

Here are the activities currently listed on my dice:

• Pick up a set of dumbbells and do some bicep curls

• Do some stretches on my yoga matt

• Use resistance bands

• Go outside and walk around my garden

• Do squats

• Hit play on an upbeat track and dance!

Sometimes, the timer going off will not be enough to get you up and moving. You may need to have a few words with your brain.

I often find myself negotiating with my brain, trying to convince myself to get up and move.

Me: “Come on, it’s time to get up.”

Brain: “Noooo! It’s nice and comfy here.”

Me: “On the count of three, we’re going to do this . . . 1 . . . 2. . . 3.”

Be gentle with your brain. Remember, it’s wired for comfort.

There’s a reason I have stretch bands hanging on door knobs, a yoga mat rolled out on my dining room floor, a rack of dumbbells next to my desk, and comfortable walking shoes always on my feet. All of these little things make it easy for me to move.

Look around your workspace: is there anything that makes it hard for you to move? Identify any barriers and do what you can to remove them.

Instead of stopping to take a movement break, can movement become part of what you do?

For instance, I wrote the first draft of this blog as I walked at a slow pace on my treadmill desk, and I edited it while pedalling at my cycle desk.

Remember, movement doesn’t need to be strenuous to be effective. Light-intensity movement delivers results.

I recently finished reading an excellent book called Creative First Aid: The science and joy of creativity for mental health. It is packed full of creative practices to help calm your nervous system.

One of the practices the authors suggest is creating a playlist of songs called ‘I Dare You Not to Move’. This playlist is a selection of songs that make you want to dance.

On a movement break, I close my blinds and hit play on one of my favourite dance tracks.

Don’t consider yourself much of a dancer? No problem! Sway your hips from side to side or throw your hands in the air and make some circles with them.

Even though it may feel good in the moment to stay seated in a comfy chair, I have to regularly remind myself that movement makes me feel good (and less stiff and achy).

Remember, whenever we force ourselves to get up and move, we go against our brain’s programming. This is why these reminders are so important.

Before stepping onto the treadmill to do a run, I say to myself, “This is good for me. You won’t regret doing this”. And you know what? I always feel better after a workout.

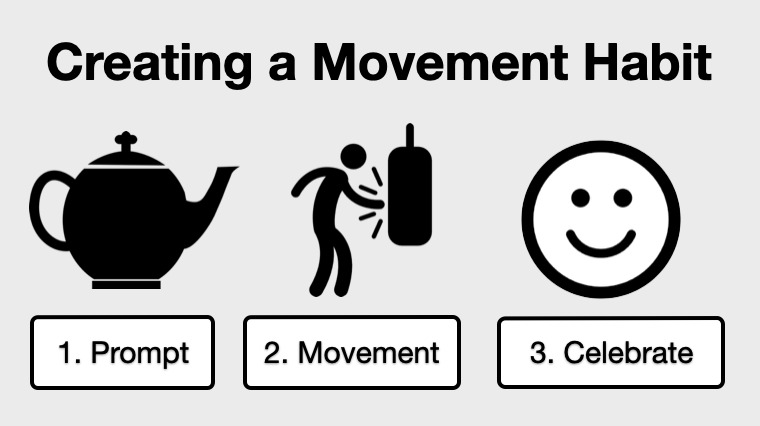

What is something you already do on a regular basis?

It could be making a cup of tea, preparing lunch, or putting on your shoes.

According to the Tiny Habits Method, the key to forming habits is to attach a tiny behaviour to a pre-existing habit. For example:

• After I put on the kettle, I will do five wall push-ups.

• After I shut down my computer, I will do arm circles for 30 seconds.

• After I put my lunch in the microwave, I will march on the spot.

• After I pick up the phone, I will stand up to walk and talk.

• After I notice I am feeling sluggish, I will hit play on an upbeat song.

If you want to wire in this new movement break quickly, celebrate after moving your body (i.e. release a positive emotion). I tell myself, “Good job Jane!”. But usually, the movement leaves me feeling good, so it’s not always necessary.

The science is in. We know breaking up periods of sitting with regular five-minute movement breaks can make a big difference to our mental and physical health. The good news is you don’t even have to break a sweat to experience these benefits (light-intensity movement will do the job).

If you can’t manage moving every half hour, no problem. Do what you can. Some movement is better than no movement. On that note, is it time to get up and move? Let’s do this together. How about a light walk? Or a short dance break?

On the count of three . . . one . . . two . . . three. Let’s go!

Share This:

When you start using this strategy, it can feel clunky and awkward. It requires some mental effort to get going.

Why can it feel hard to start mind mapping?

Because it isn’t a habit (not yet, anyway). But once mind mapping becomes a habit, it can feel easy and deeply rewarding.

So, how do you get to that point where mind mapping feels easy? Even fun?

In this article, I will explore how you can create a habit of mind mapping. I’ll show you how to remove friction or pain points so it’s much easier to put pen to paper and absorb ideas.

Let’s start by looking at what gets in the way and stops many people from creating mind maps in the first place. I’ll also share some strategies you can use to overcome each of these barriers.

When you look at a mind map with all the pictures and different colours, it seems like something that would take a fair amount of time and effort to create.

If you’re comparing mind mapping to the time it takes to read your book passively, then yes, mind mapping will take more time. But you need to understand that reading your book passively is not an effective way to learn. In contrast, mind mapping is super effective.

People often fall into the trap of trying to make their mind maps look like works of art. Try lowering your standards and allowing yourself to make a mess when you mind map. This will speed up the process.

Another time trap is trying to mind map as you read and trying to mind map everything you read. I find it’s much faster to read and tab key ideas worth mind mapping later on. Once I’ve finished reading either the chapter or book, I then commence the mind mapping process. By this stage, I have a better understanding of the key ideas and what’s worth mind mapping.

Some people get hung up on the way their mind maps look. They can’t stand looking at messy pictures and scribbled words. If that’s you, perhaps you could take your drawing skills to the next level with some practice and sketch classes. But it’s not necessary.

Mind maps are not there to look pretty. They are there to help you learn. I am a big fan of badly drawn mind maps. If you look at my mind maps from university, they’re not works of art but they contain loads of important ideas. And that’s what matters most when it comes to learning.

Here’s a simple hack: invest in a set of nice, vibrant coloured pens. A bit of colour on the page will make your mind maps more visually appealing.

Mind mapping is straightforward. You draw a central image, curved lines, a few pictures, and write down key ideas. That’s it!

It’s not something you need to read a book about. You don’t need to enrol in a 10 week program to learn how to do this.

If you want some tips on how to mind map, check out my free Mind Mapper’s Toolkit. It’s a quick and easy read.

It’s important to realise that the first time you engage in any new behaviour, it will most likely feel strange and uncomfortable. You may feel a bit clumsy and awkward. You may have questions, “Am I doing this right?”. All of this is normal and to be expected.

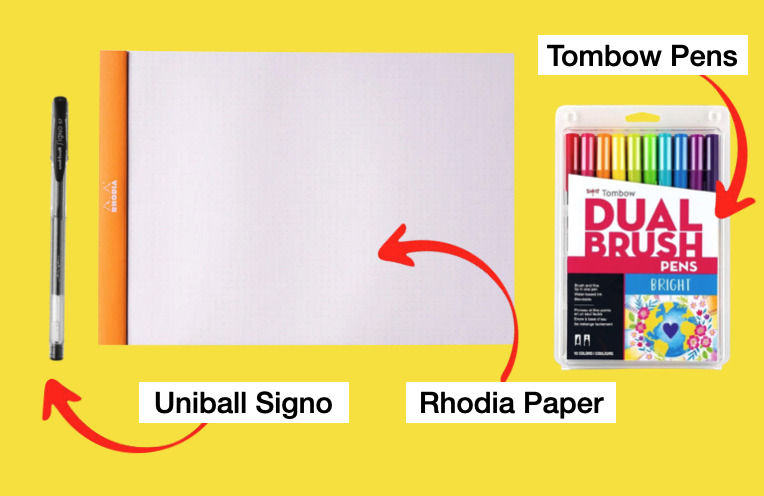

Even something as simple as the pen you mind map with can make or break the mind mapping process.

You’ve probably noticed that some pens don’t feel pleasant to write or draw with. For instance, I’m not a fan of the popular Sharpie pen range. I don’t like the way these pens bleed through the page. And I really don’t like the way they smell.

These may seem like minor irritations and quirks, but trust me, they’re not. Your mind mapping experience will be diminished by a pen that doesn’t feel good in your hand or on the page. And any behaviour that feels unpleasant is much harder to sustain.

I’ve since ditched my Sharpie pens. I mind map with a uniball signo pen and non-toxic Tombow paintbrush pens. As far as coloured pens go, I won’t lie, these pens are pricey! But you can find them online for $25 cheaper than in Officeworks (a big stationery store in Australia).

What I love about these pens is that they are super easy to use, feel lovely to strike across the page, and they won’t leave you with a splitting headache from the ink smell.

Here are some things that have helped me to establish this habit in my life:

When is the best time for you to mind map? Where in your day can you easily slot in a 15 minute mind mapping session?

I like to mind map when I feel fresh and mentally alert (first thing in the morning).

Find an activity that you do every day without fail (e.g., having a shower, eating breakfast or dinner) and use that to prompt you to start a mind mapping session.

For instance, after I have completed my morning routine (workout, breakfast and shower), that’s my cue to sit down and start mind mapping.

Before you start your session, set yourself up with everything you need to mind map. I like doing this the night before my morning mind mapping sessions.

Before I go to bed, I lay out a sheet of A3 paper, my pens, and my timer. The book I am mind mapping is open on the page where I need to start working. The next day, all I need to do is sit down, start my timer, pick up a pen, and away I go!

What’s one thing that can slow down the mind mapping process?

For me, it’s digital distractions (e.g., text messages and notifications).

You probably already know the things that tend to derail you. Create a barrier between you and those things.

For example, my phone is the biggest distraction for me. How do I deal with this? Before I start mind mapping, I take my phone and place it away from my body in another room.

This signals to my brain that my phone is off-limits and it’s time to knuckle down and focus on my work.

Don’t wait until you feel pumped and inspired to create a mind map. Set a timer for 10-15 minutes and start mind mapping (regardless of how you feel).

If you miss a day, don’t beat yourself up. It’s no big deal. Just say to yourself, “Tomorrow is a new day. I will get back into mind mapping then”.

When the timer goes off at the end of your mind mapping session, say to yourself, “Good job!”. Do anything that makes you feel instantly good. I often clap my hands or do a fist pump.

According to Professor BJ Fogg, the secret to wiring in any new habit is to release a positive emotion within milliseconds of engaging in the new behaviour. When you release positive emotions, this releases dopamine in your brain. This makes it more likely that you’ll engage in this behaviour again.

I mentioned this before, but it’s important to repeat it: don’t go cheap with your mind mapping tools. Invest in good pens and paper. My favourite pens for mind mapping are uniball signo pens (0.7 tip) and Tombow paintbrush pens. Regarding paper, I love using Rhodia paper (it feels like your mind mapping on butter).

It may sound a little dramatic, but mind mapping changed my life. I used to read books and then feel frustrated that I couldn’t retain much information. But now, I have a strategy I can easily use to help me understand and remember complex ideas. This gives me confidence when it comes to learning new skills and information.

I encourage you to be playful with this strategy. Don’t get too hung up on how your drawings look. Your top priority is to leave perfectionism at the door and have some fun. Because when it comes to mind mapping, done is better than perfect.

Years ago, I was gifted a treadmill.

Within days of receiving this treadmill, I had converted it into a walking desk. I was super excited by the possibility of walking and working simultaneously (one form of multitasking I’m totally fine with).

I had visions of myself walking and working with supercharged productivity. I thought, “Nothing is going to stop me!”.

But despite my best intentions, I struggled to use this treadmill desk. I couldn’t make walking and working part of my daily routine.

I’m embarrassed to admit that this treadmill just sat there collecting dust for years.

Occasionally, I would hop on the treadmill to practice my presentations (10 minutes here and there), but this was not a solid part of my daily routine like I had hoped it would be.

It wasn’t a lack of information. I was fully aware of the benefits of movement for learning.

I had read dozens of books and research papers that provided solid evidence for the benefits of incorporating movement into the day.

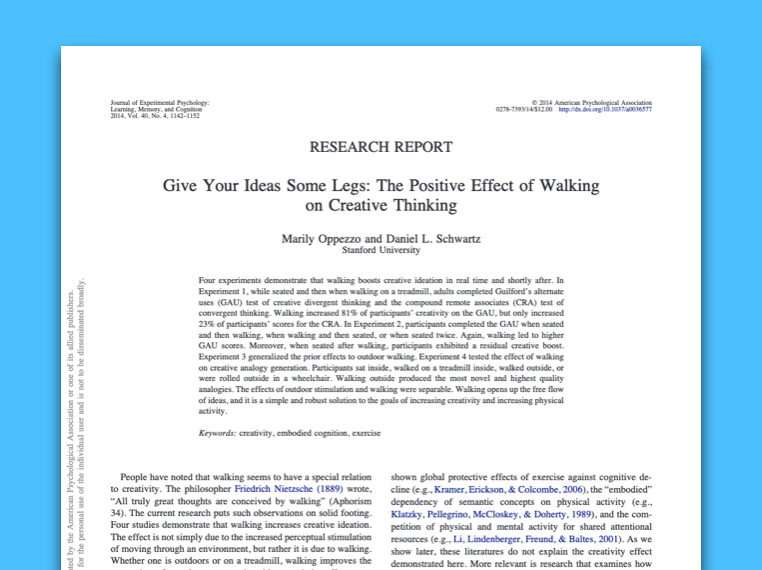

For example, the Stanford university research study called Give your ideas some legs showed that people who walked generated more creative ideas than those who sat.

I had also experienced firsthand the powerful benefits of movement: it made me feel better, stronger, and mentally sharper.

Something else was getting in the way.

So, I asked myself what Professor BJ Fogg would call the Discovery Question:

What is making this behaviour (i.e., walking and working at my treadmill desk) hard to do?

In his book Tiny Habits, Behavior Design expert Professor BJ Fogg argues if you’re struggling to engage in a particular behaviour, it will be due to one of five factors: 1) Time, 2) Money, 3) Physical effort, 4) Mental effort, and 5) Routine.

He calls these five factors the Ability Chain.

To pinpoint where you are stuck with adopting a new behaviour, Professor Fogg recommends asking the following questions:

• Do you have enough time to do the behaviour?

• Do you have enough money to do the behaviour?

• Are you physically capable of doing the behaviour?

• Does the behaviour require a lot of creative or mental energy?

• Does the behaviour fit into your current routine, or does it require you to make some adjustments?

Professor Fogg states:

“Your ability chain is only as strong as its weakest Ability Factor link.”

It was the physical effort link.

My problem was that I was walking way too fast on my treadmill, which caused my legs to fatigue quickly.

I also felt uncomfortable having to look down at my small laptop screen.

After asking the discovery question, it became clear why this habit had not stuck: I felt awkward and clumsy using my treadmill desk.

But it also became apparent that I could strengthen this weak link by making simple adjustments.

I then asked myself this question:

What could make using my treadmill desk easier to do?

I brainstormed ways to improve my treadmill desk (How could I make it easier to walk and work simultaneously?). With a bit of experimentation and a playful mindset, I was amazed that after years of this treadmill collecting dust, I was finally using it regularly.

I experienced what author Jenny Blake would call a nonlinear breakthrough (NBL).

In her book Free Time, Blake describes a non-linear breakthrough as “an unexpected sharp turn of clarity or success, rather than a linear, long, or otherwise time-consuming analysis or slog”.

This habit of using my treadmill desk was wired in quickly, easily, and joyfully.

If you’re interested in using a treadmill desk and feeling less exhausted at the end of the day, I recommend trying the following things.

Like any new habit, start small. If you’re used to sitting all day, this transition will take some time. Most people would struggle to go from sitting to walking all day. My advice is to ease into it.

Start by doing mini treadmill work sessions (15-30 minutes or whatever you can manage) and gradually build your way up to longer sessions (1 hour).

In the first couple of weeks of developing this habit, I used my treadmill desk in the morning for 2 to 3 hours and then gave myself permission to use my sit-stand desk in the afternoon.

As I became more confident walking and working, I replaced more sit-stand sessions with treadmill desk sessions. The treadmill desk is now my main workstation and the sit-stand desk is rarely used.

Comfort is king. Anyone who works in a job where they are on their feet all day will tell you that comfortable shoes are an absolute must. Don’t skimp on good shoes.

I went to a sports store and purchased a pair of running shoes that provided excellent support and made my feet feel good all day. I live in these shoes now, and they make walking and working easier and more enjoyable.

I’m a fast walker. But it’s difficult (and tiring) to walk and work at a fast pace. You can’t sustain that pace all day. It’s also hard to type and focus on your work when power walking.

I read in online forums that professional treadmill desks (not DIY ones like mine) are programmed to go at a slow pace. This is a deliberate design decision. The slow pace is not only for your safety but also so you can sustain the habit of walking and working for a long time.

I’ve had to learn to slow down (not just at my treadmill desk but in all areas of my life). Once I recalibrated to walking at a much slower pace, I could sustain this habit of working in this new way.

Some days, you’re going to have more energy than others. If you’ve been walking for 30 minutes and feel like your legs need a break, give yourself permission to take a break.

Using a treadmill desk shouldn’t feel like a chore. It should be viewed as an activity that makes you feel more alert and energised. Using a treadmill desk (even a budget homemade one) is a privilege!

You need to get the ergonomics right to sustain the habit of using a treadmill desk. In other words, you need to be comfortable at your treadmill desk.

In hindsight, it’s obvious why I wasn’t using my treadmill desk for years: my setup wasn’t the best. I was looking at a tiny laptop screen with my neck craned and moving at a power walker’s pace.

I wasn’t comfortable, which meant I didn’t feel good.

And if you don’t feel good doing something, it’s much harder to sustain a particular behaviour. You may also end up with bigger problems down the track (e.g., bad posture and lower back problems).

A couple of years ago, I attempted to improve the ergonomics of my treadmill desk by placing a sit-stand desk on top of my existing desk. I also propped up a slightly bigger monitor on some books.

This setup turned out to be disappointing. My monitor would shake as I walked on the treadmill. The sit-stand desk also restricted my walking range on the treadmill belt. Again, this setup was far from ideal and the habit of using it didn’t stick.

A few months ago, while researching ways to improve my treadmill desk, I came across forum posts where people shared that they had mounted a monitor to their wall and used it with their treadmill desk. Bingo! Immediately, I knew this was the solution for me.

I jumped on Gumtree and found a secondhand large monitor and monitor bracket. This created more space on my desk for other items (paper, pen, and my stream deck).

Finally, I could say goodbye to terrible posture and squinting at tiny icons on a small laptop screen.

My treadmill desk also doubles as my high-intensity exercise station. Each morning, before I launch into my workday, I warm up my brain by doing a 20-30 minute walk + run to clear my mind and improve my mood.

When I first started doing these morning runs, I noticed whenever I reached high speeds, objects in the cupboard next to the treadmill would shake and sometimes fall off onto the treadmill belt, creating potential trip hazards.

To solve this problem, I got a roll of heavy-duty Bear tape and taped all the boxes to the shelves beside me. It may not look pretty, but it keeps all my items securely in place.

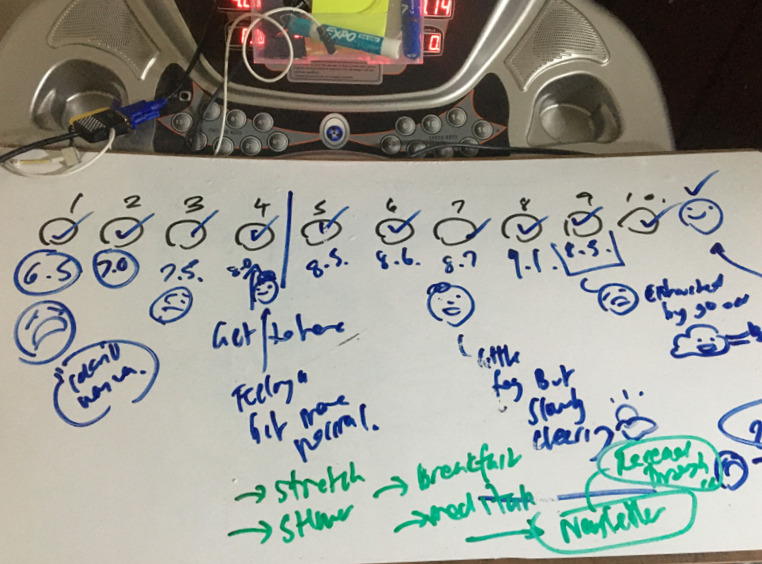

I noticed that as I ran on the treadmill, creative ideas would come to me out of nowhere. I needed a way to capture these ideas.

So, I turned my treadmill desk into a whiteboard. This cost $5. Here’s what I did . . .

I found a roll of whiteboard wallpaper at Officeworks (a big stationery shop in Australia) and covered my desk (an old plank of wood) with it.

I also attached a plastic container to the treadmill that I found at the tip shop for $1. This container holds whiteboard markers, sticky notes, and pens.

Whenever an idea strikes, I get a whiteboard marker and write it on my desk. At the end of my run, I transfer any good ideas into my notebook.

Some people work and learn best when they move their bodies. I’m one of those people. If you’re like me and need to move, it is worth spending time getting your work set up right. The important thing is that you approach this with an open mind.

Some things will work, and some won’t. But keep tinkering and tweaking until you find a working setup, rhythm, and pace that feels good. You’ll be amazed by how much more energised and alert you feel when incorporating more movement into your day.

I understand this cringe factor.

In high school, goal setting felt forced. I’d think, “Why are they making me do this?” and “What’s the point?”.

However, once I got to university, I realised that goals are a helpful life strategy.

In this article, I want to share my perspective on goal setting and how this strategy has helped me to get things done.

I’m going to tell you:

• What goals are

• Why you’d want to have them

• How to stick at them

• Why you need to protect your goals from destructive outside forces

Let’s go!

Goals are things you want to do. Perhaps you want to write a book, jog around the block every morning, start a podcast, get a part-time job to save money or learn to play an instrument. These are goals.

• Goals give your life a sense of purpose

• Goals give your life meaning and a reason to get out of bed

• Goals help to focus your mind on what you want/need to do

• Goals help you to create a better, less boring life

As Giovanni Dienstmann explains in his book Mindful Self Discipline:

“We all need to aspire to something and feel that we are going somewhere. Otherwise, there is a sense of boredom in life. Our daily routine feels stale and unengaging. As a result, we seek relief through bad habits, and seek engagement through mindless entertainment, news, social media, games, etc.”

Have you ever set a goal, you felt excited, but then that excitement quickly dissipated, and you gave up on the goal?

Whenever this happens, it’s easy to think, “Goal setting doesn’t work!”.

However, the problem isn’t with goal setting as a strategy.

The problem is that motivation is completely unreliable (it comes and goes). Plus, you were probably never taught how to achieve your goals in the first place.

In other words, you were set up to fail.

There’s a lot of pretty average advice out there about goal setting. I’ve heard dozens of goal setting pep talks, and many can be summed up like this:

“Set a goal, make it SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound), break it down, blah, blah, blah.”

Most students tune out when they hear these pep talks. You can feel the energy being sucked out of the room.

This advice doesn’t work for most people. And it’s incomplete.

I’ve found that the following simple ideas can make a big difference in helping you move from inaction to action when it comes to pursuing your goals:

Achieving big long-term goals requires consistently engaging in small behaviours over time. You need to chip away and develop habits to get there.

For instance, after taking a hiatus from writing books (because I felt stuck and overwhelmed by the idea), I finally started writing down my ideas.

By starting small.

I told myself all I had to do was open the Word document and write one sentence. And the sentence didn’t even have to be good! But I had to do this every single day.

If I wanted to write more than one sentence, I could. But one sentence was my absolute minimum. Most days, I wrote at least a paragraph. But when I didn’t feel great, I would show up and write one sentence.

Nine months later, I had a draft manuscript ready to send to my editor.

Many different behaviours can help you achieve your goal. The first step is to brainstorm all the possible behaviours that can help you move closer to it.

One way to do this is with BJ Fogg’s tool, Swarm of Behaviors (also known as Swarm of Bs).

Here’s what you do:

You write your goal/aspiration/outcome (whatever you want to achieve) in the middle of a sheet of paper. Then, you spend a few minutes listing all the behaviours that will help you achieve it.

Dr Fogg stresses:

“You are not making any decisions or commitments in this step. You are exploring your options. The more behaviors you list, the better.”

When I was brainstorming behaviours that could help me to write my next book, I came up with the following list:

1. Use an Internet blocker app and block myself from distracting websites

2. Carry a notepad and pen with me everywhere I go (to capture ideas)

3. Write one sentence every morning

4. Speak my ideas into a voice recorder when I go for a walk

5. Use the Write or Die app

6. Manage my inner critic (when it strikes, say to myself, “It can’t be all bad!”)

7. Give myself a pep talk each day (e.g., “Done is better than perfect!”)

8. Do Julia Cameron’s morning page activity (i.e., free writing)

9. Attend a writing retreat

10. Sign up for the ‘Turbocharge your writing’ course

11. Pick up a mind map, select an idea and use it as a writing prompt

Once you’ve finished brainstorming potential behaviours, go through your list and select just a few behaviours to get the ball rolling (I selected #1, #3, and #6).

It’s well worth spending a couple of minutes making each of these behaviours ‘crispy’ (i.e., specific). For instance, for Behaviour #1, I decided which websites I would block myself from using and at what times.

When we work towards big life goals, the process is never neat or linear. Showing up and doing whatever you need to do (even just writing one sentence) can feel like a daily grind. Mild discomfort usually infuses the whole process.

Accept that’s how it is. It will sometimes feel like a hard slog, but the rewards are worth it.

The long-term rewards of working on your goals far outweigh the superficial rewards of scrolling through social media, watching Netflix, etc.

Even if you don’t achieve what you initially set out to do, chances are you’ll still be better off than you were before. Why? Because you’ll have learnt a bunch of new skills and life lessons.

Be careful who you share your goals with. Some people delight in stamping all over your goals and crushing your hopes and dreams.

For example, when I was 10 years old, I started attending drama classes outside of school. These classes were a lot of fun and quickly became the highlight of my week.

I remember thinking, “When I grow up, I want to run a drama academy to help boost kids’ confidence”.

I felt inspired by this idea. Drama had helped me come out of my shell and I wanted this for other kids who were lacking confidence. So, I decided to be brave and share my plans with my primary school teacher at the time.

I was expecting Mr D to say, “Good for you, Jane!”. But instead, he said with a smirk, “How do you think you’re going to do that?”

And then he started grilling me with questions . . .

“Where will you get the money from to set this up?”

“Who is going to come to your classes?”

“Where do you plan on running these classes?”

On and on Mr D went.

Ugh. “Just stop Mr D!” I wanted to scream.

I was left feeling crushed.

So, take it from me: Be careful who you share your goals with. Because some people get a kick out of squashing stuff (e.g., your dreams).

But nowadays, there’s a more powerful (and often overlooked) force that can mess with your goals: social media

If you’re constantly checking social media and looking at what other people are doing, that’s time and energy you could have spent working towards your goals. But that’s only part of the story . . .

Social media exposes you to a hodgepodge of content: the best bits of people’s lives, advertising, conspiracy theories, and outrage-inducing influencers. All this noise messes with your goals by subtly shifting and changing your worldview, beliefs, attitudes, and what you view as important in life.

In his brilliant book Stand Out of Our Light: Freedom and Resistance in the Attention Economy, ex-Google strategist and now Oxford-trained philosopher James Williams shares his struggles with this. He states:

“. . . I felt that the attention-grabby techniques of technology design were playing a nontrivial role. I began to realise that my technologies were enabling habits in my life that led my actions over time to diverge from the identity and values by which I wanted to live. It wasn’t just that my life’s GPS was guiding me into the occasional wrong turn, but rather that it had programmed me a new destination in a far-off place that it did not behoove me to visit. It was a place that valued short-term over long-term rewards, simple over complex pleasures.”

He adds:

“…I found myself spending more and more time trying to come up with clever things to say in my social posts, not because I felt they were things worth saying but because I had come to value these attentional signals for their own sake. Social interaction had become a numbers game for me, and I was focused on “winning” – even though I had no idea what winning looked like. I just knew that the more of these rewarding little social validations I got, the more of them I wanted. I was hooked.

. . . I had lost the higher view of who I really was, or why I wanted to communicate with all these people in the first place.”

When you go on social media, you need to realise that there are thousands of highly intelligent people on the other side of the screen and it’s their job to figure out how to capture and exploit your attention.

In short, the values and goals of these big tech companies are not aligned with your values and goals. Facebook’s first research scientist Jeff Hammerbacher summed it up nicely when he said:

“The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads . . . and it sucks.”

Take a moment to think of the people who you admire. How would you feel if you saw them spending vast amounts of time distracted and obsessed with social media?

I’ll leave you with this powerful quote from author Adam Gnade:

“Would you respect them [your biggest hero] as much if you saw them hunched over their phone all day like a boring zombie? No, you want them out there in the world doing heroic things, writing that great novel/song/whatever, saving the planet, standing up for the disenfranchised, or whatever else it was that made you love them in the first place. Let’s try to be as good as our heroes.”

Whatever you want in life, work out what you need to do to get there (i.e., the concrete behaviours), and then roll up your sleeves and get started.

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive sessions on learning to learn, combating procrastination, exam preparation, how to focus in the age of distraction, habit formation and much, much more!

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to our newsletter:

© 2024 Learning Fundamentals