• Highlight or underline your books?

• Test yourself with flash cards?

• Create notes?

• Make an outline of the key topics?

• Reread your books and/or notes?

These are all popular study strategies and exam revision techniques. But how effective are they? And could you do them better?

In their paper, cognitive psychology researchers Miyatsu et al (2018) examined how students can optimise the use of the following five study strategies:

1. Note-taking

2. Rereading

3. Marking (Underlining or highlighting)

4. Outlining

5. Flash cards

Do you have a tendency to write down word for word what the teacher says?

It’s best to summarise or paraphrase the information. Put it in your own words.

Do you prefer to take notes with pen and paper or on a laptop?

Taking notes by hand is best.

Why? Because you can’t write as fast as the teacher speaks, so you’re more likely to capture the information in your own words.

But when students take notes on a laptop they usually can type as fast as the teacher speaks. So what happens is you get a word for word script of what the teacher said. The problem is you don’t remember as much of the information when you take notes this way.

But regardless of whether you take notes by hand or on a laptop …

Don’t let your notes just sit there. Work with them. Transform them into pictures and flash cards. Scribble questions and other ideas all over them.

If I need to commit information to memory, I always do one or more of the following:

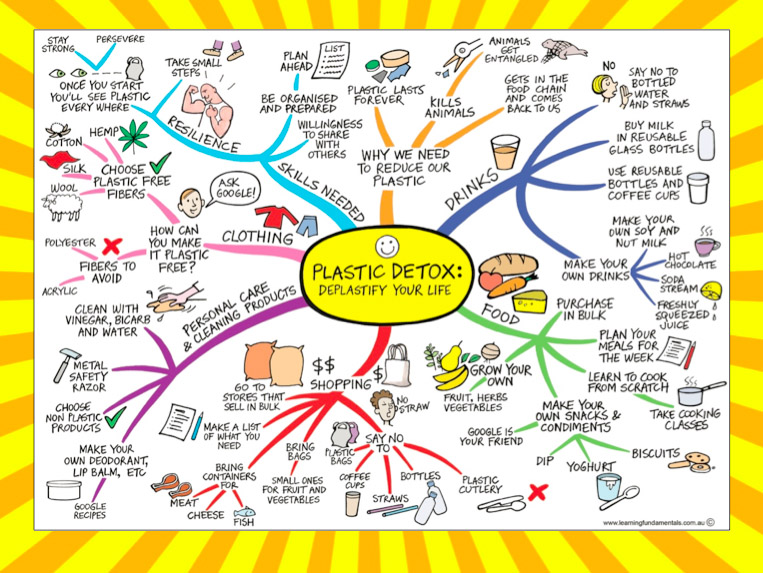

• Mind map out my linear style notes

• Put key points onto flash cards

• Transform them into practice tests

Miyatsu et al (2018) state:

“Reviewing is crucial in reaping the full benefits of note-taking.”

Remember, your notes are pretty much useless unless you review them.

I’m not a fan of reading passively.

If I’m reading complex information, I block out distractions (e.g. turn off music and put my phone in another room) and I draw pictures as I read. When I read this way, there’s usually no need to reread.

But if you reread passively (e.g. no drawing), try doing the following to make the ideas stick:

Space out the first and second reading by a few days. Research shows this produces more durable learning.

Before rereading, try doing retrieval practice. Retrieval practice is when you force yourself to bring information to mind (without looking at your books and notes).

Retrieval practice has been identified it as the number one study strategy. Use retrieval practice and you’ll dominate your subject areas.

1. Use a blank piece or paper or a whiteboard to write down all the things you can remember on the topic.

2. Try explaining to a friend, the wall or a pet what you can remember on the topic.

3. Use flash cards to test yourself.

Tip: It’s okay to retrieve the wrong information, just as long as you correct yourself.

So make sure you check to see that you are retrieving the correct information. It’s critical!

This isn’t a good study strategy to use. It gives you a false sense of confidence. You think the information has transferred from the page into your brain, but usually it hasn’t.

But if you really must highlight, you need to exercise some serious restraint with yours pens.

Read a section of the text first to get a sense of the important ideas (no pens allowed). Only after you have read the section are you allowed to underline the key ideas.

Personally, I think it’s more effective to draw pictures in the margins or on a blank sheet of paper as you read.

Please don’t make highlighting or underlining your only study strategy. As the Miyatsu et al (2018) state:

“Marking should not be students’ only preparation method for higher-order assessments.”

You know how your books have a contents page? Outlining is where you create a contents page for a subject.

Do you have a syllabus or unit outline for each of your subjects? If you do, check the unit content section. Boom! That’s your outline.

Don’t have an outline? Create one for a subject/topic. This will give you a sense of the key ideas and how they are structured.

Here’s another way you can do retrieval practice using an outline …

Use your outline to test yourself.

Go through each topic and see how much you can remember (“What do I know about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs?”).

Get easily overwhelmed by a long list of topics? No problem!

Simply use a blank piece of paper to cover up the topics. Then proceed through the topics, one by one, shifting the paper down the page as you successfully bring to mind information on each point.

If you use flash cards correctly, this is a great way to do retrieval practice.

Use your flash cards to test yourself.

But here’s the thing: don’t just read the question and then flip and read the answer straight away. Try bringing the information to mind before you flip the card over.

It’s tempting to want to drop a card when you get the answer correct (“I know that!”). But hold onto that card. Keep it in your pile of flash cards. Only drop a card after you have successfully retrieved the correct information at least three times. Remember, the aim is to strengthen the information in your mind so you can easily recall it later on.

While you’re at it, space out your practice. Go through a pile of flash cards and then take a break before practicing them again (my recommendation is to wait at least 24 hours).

Continuously drilling your flash cards is not an effective way to study.

After completing a set of flash cards, go outside and get some fresh air, make yourself a smoothie, etc. Do something good for yourself. Your brain deserves a break.

Note: For learning more complex information, flash cards may not be the best strategy to use. I prefer drawing the information out first and then creating flash cards for key concepts on the mind map.

So there you have it! Various ways to optimise five popular study strategies.

Just remember, if you want to save time and elevate your studies, you are better off using strategies that have been found to be highly effective (click here to read more about highly effective study strategies).

But if you’re in the habit of using the popular strategies mentioned above, that’s okay! Why not make some small tweaks and try adding some more effective strategies into your study routine?

While they may not feel as good and easy as highlighting, they will certainly fast track your studies and boost your performance.

Share This:

When you start using this strategy, it can feel clunky and awkward. It requires some mental effort to get going.

Why can it feel hard to start mind mapping?

Because it isn’t a habit (not yet, anyway). But once mind mapping becomes a habit, it can feel easy and deeply rewarding.

So, how do you get to that point where mind mapping feels easy? Even fun?

In this article, I will explore how you can create a habit of mind mapping. I’ll show you how to remove friction or pain points so it’s much easier to put pen to paper and absorb ideas.

Let’s start by looking at what gets in the way and stops many people from creating mind maps in the first place. I’ll also share some strategies you can use to overcome each of these barriers.

When you look at a mind map with all the pictures and different colours, it seems like something that would take a fair amount of time and effort to create.

If you’re comparing mind mapping to the time it takes to read your book passively, then yes, mind mapping will take more time. But you need to understand that reading your book passively is not an effective way to learn. In contrast, mind mapping is super effective.

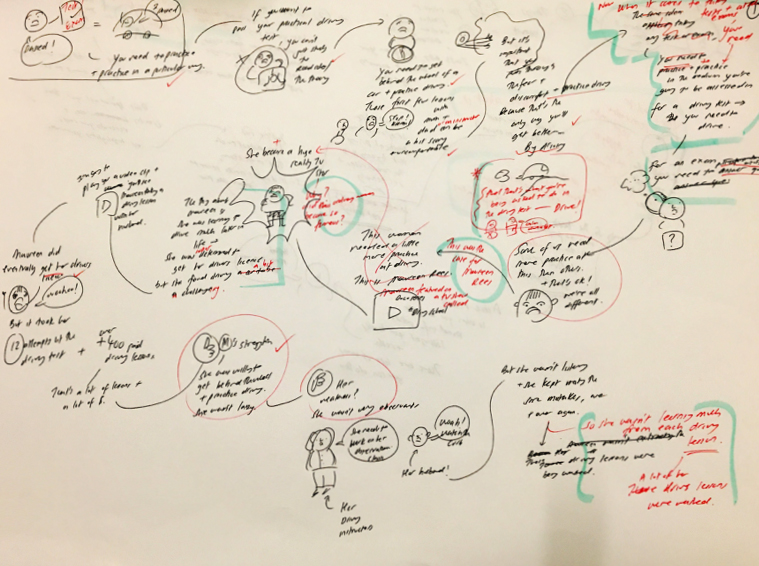

People often fall into the trap of trying to make their mind maps look like works of art. Try lowering your standards and allowing yourself to make a mess when you mind map. This will speed up the process.

Another time trap is trying to mind map as you read and trying to mind map everything you read. I find it’s much faster to read and tab key ideas worth mind mapping later on. Once I’ve finished reading either the chapter or book, I then commence the mind mapping process. By this stage, I have a better understanding of the key ideas and what’s worth mind mapping.

Some people get hung up on the way their mind maps look. They can’t stand looking at messy pictures and scribbled words. If that’s you, perhaps you could take your drawing skills to the next level with some practice and sketch classes. But it’s not necessary.

Mind maps are not there to look pretty. They are there to help you learn. I am a big fan of badly drawn mind maps. If you look at my mind maps from university, they’re not works of art but they contain loads of important ideas. And that’s what matters most when it comes to learning.

Here’s a simple hack: invest in a set of nice, vibrant coloured pens. A bit of colour on the page will make your mind maps more visually appealing.

Mind mapping is straightforward. You draw a central image, curved lines, a few pictures, and write down key ideas. That’s it!

It’s not something you need to read a book about. You don’t need to enrol in a 10 week program to learn how to do this.

If you want some tips on how to mind map, check out my free Mind Mapper’s Toolkit. It’s a quick and easy read.

It’s important to realise that the first time you engage in any new behaviour, it will most likely feel strange and uncomfortable. You may feel a bit clumsy and awkward. You may have questions, “Am I doing this right?”. All of this is normal and to be expected.

Even something as simple as the pen you mind map with can make or break the mind mapping process.

You’ve probably noticed that some pens don’t feel pleasant to write or draw with. For instance, I’m not a fan of the popular Sharpie pen range. I don’t like the way these pens bleed through the page. And I really don’t like the way they smell.

These may seem like minor irritations and quirks, but trust me, they’re not. Your mind mapping experience will be diminished by a pen that doesn’t feel good in your hand or on the page. And any behaviour that feels unpleasant is much harder to sustain.

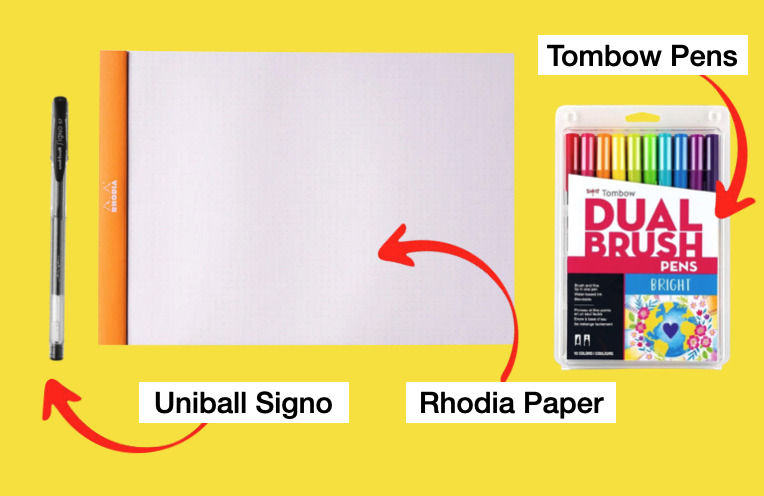

I’ve since ditched my Sharpie pens. I mind map with a uniball signo pen and non-toxic Tombow paintbrush pens. As far as coloured pens go, I won’t lie, these pens are pricey! But you can find them online for $25 cheaper than in Officeworks (a big stationery store in Australia).

What I love about these pens is that they are super easy to use, feel lovely to strike across the page, and they won’t leave you with a splitting headache from the ink smell.

Here are some things that have helped me to establish this habit in my life:

When is the best time for you to mind map? Where in your day can you easily slot in a 15 minute mind mapping session?

I like to mind map when I feel fresh and mentally alert (first thing in the morning).

Find an activity that you do every day without fail (e.g., having a shower, eating breakfast or dinner) and use that to prompt you to start a mind mapping session.

For instance, after I have completed my morning routine (workout, breakfast and shower), that’s my cue to sit down and start mind mapping.

Before you start your session, set yourself up with everything you need to mind map. I like doing this the night before my morning mind mapping sessions.

Before I go to bed, I lay out a sheet of A3 paper, my pens, and my timer. The book I am mind mapping is open on the page where I need to start working. The next day, all I need to do is sit down, start my timer, pick up a pen, and away I go!

What’s one thing that can slow down the mind mapping process?

For me, it’s digital distractions (e.g., text messages and notifications).

You probably already know the things that tend to derail you. Create a barrier between you and those things.

For example, my phone is the biggest distraction for me. How do I deal with this? Before I start mind mapping, I take my phone and place it away from my body in another room.

This signals to my brain that my phone is off-limits and it’s time to knuckle down and focus on my work.

Don’t wait until you feel pumped and inspired to create a mind map. Set a timer for 10-15 minutes and start mind mapping (regardless of how you feel).

If you miss a day, don’t beat yourself up. It’s no big deal. Just say to yourself, “Tomorrow is a new day. I will get back into mind mapping then”.

When the timer goes off at the end of your mind mapping session, say to yourself, “Good job!”. Do anything that makes you feel instantly good. I often clap my hands or do a fist pump.

According to Professor BJ Fogg, the secret to wiring in any new habit is to release a positive emotion within milliseconds of engaging in the new behaviour. When you release positive emotions, this releases dopamine in your brain. This makes it more likely that you’ll engage in this behaviour again.

I mentioned this before, but it’s important to repeat it: don’t go cheap with your mind mapping tools. Invest in good pens and paper. My favourite pens for mind mapping are uniball signo pens (0.7 tip) and Tombow paintbrush pens. Regarding paper, I love using Rhodia paper (it feels like your mind mapping on butter).

It may sound a little dramatic, but mind mapping changed my life. I used to read books and then feel frustrated that I couldn’t retain much information. But now, I have a strategy I can easily use to help me understand and remember complex ideas. This gives me confidence when it comes to learning new skills and information.

I encourage you to be playful with this strategy. Don’t get too hung up on how your drawings look. Your top priority is to leave perfectionism at the door and have some fun. Because when it comes to mind mapping, done is better than perfect.

Research shows active recall (aka retrieval practice) is a highly effective strategy for remembering information. This strategy will take your studies and your grades to the next level.

Active recall involves bringing information to mind without looking at your books and notes.

I have spent the last 30 days experimenting with this excellent learning strategy. In this blog, I’ll share what I did and how I kept the process interesting for my brain.

I no longer need to study for tests and exams.

So, why did I spend 30 days using active recall strategies?

In my line of work, I need to constantly come up with new and original content to present to students. I also need to memorise this content. Why?

Because if I was to read from a sheet of notes or text heavy slides that would be really boring for students. I want to connect with students and to do this, I have to be able to deliver the content off the top of my head with speed and ease.

This is where active recall enters the picture.

Active recall helps to speed up the learning process. It allows you to learn more in less time.

Below I share some of the ways I use active recall to learn new presentation content. Keep in mind, you can use all of these strategies to prepare for an upcoming test or exam.

Whiteboards are wonderful learning tools. Here’s how I use a whiteboard to do active recall . . .

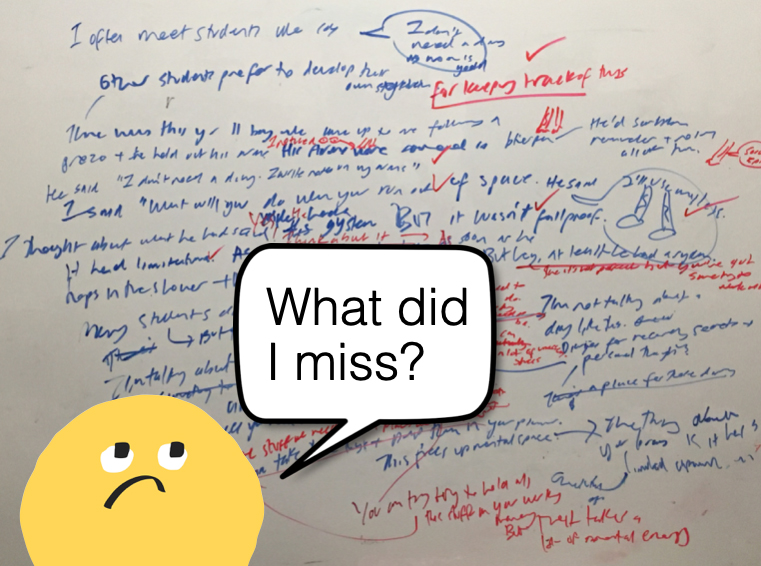

I push my speech notes to the side, so I can’t look at them. Then I grab a marker and say to myself, “What can you remember? Go!”.

I write out everything I can remember on the whiteboard. Once I’ve exhausted my memory, I pick up my notes and check to see how I went (using a red marker to make corrections).

No whiteboard? No problem!

I pick up a pen and sheet of paper and start scribbling out whatever I can remember on the topic. When I get stuck, I pause and take a few deep breaths as I try to scan my brain for the information.

I regularly remind myself that it is okay to not remember the content. “This is how the process goes!”, I say to myself. There is no point beating myself up. That only leads to feelings of misery and not wanting to do active recall practice.

After having a shot at it, I take out my notes, pick up a red pen, and begin the process of checking to see how I went.

Sick of writing? I get it.

Try drawing out the information instead. Alternatively, you can use a combination of words and pictures, which is what I often do.

Grab a blank piece of paper (A3 size is best) and create a mind map of everything you can remember on a topic (no peeking at your notes). Then check your notes or the original mind map to see what you remembered correctly and incorrectly.

Writing and drawing out information can take time. If you want to speed up the process, you can talk to yourself.

But don’t do this in your head. It’s too easy to just say “Yeah, yeah, I know this stuff!”. You need to speak it out loud as this forces you to have a complete thought. Then, check your notes to see how you went.

The only downside with this approach is you don’t have a tangible record of what you recalled, which brings me to the next strategy . . .

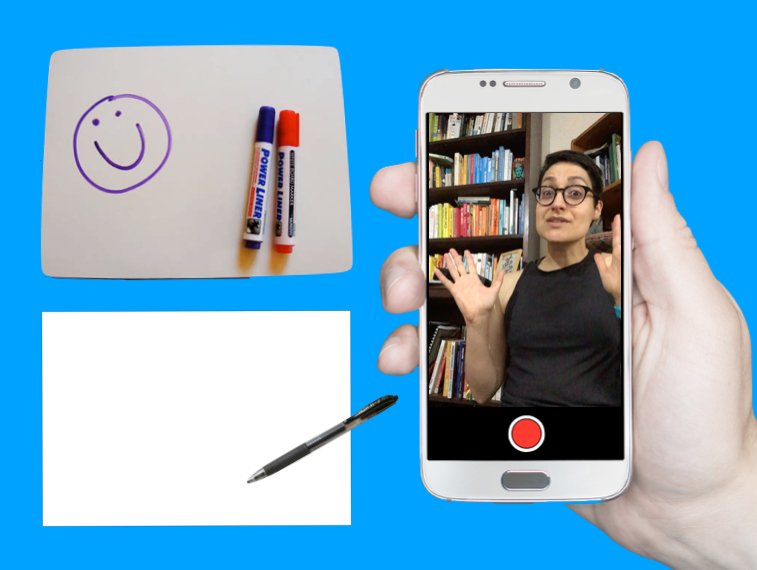

I make videos of myself presenting the content (without referring to my notes). Although I use special software and tools to make my videos, you don’t need any fancy equipment. Your phone will do the job. Here’s what you can do . . .

Set your phone up so the camera is facing you. Now hit the record button and tell the camera what you’re going to do active recall on. Have a shot at explaining the idea. Then stop recording and hit the play button.

Watching yourself struggle to remember information is often hard viewing. But this is where it’s super important to double down on telling yourself kind thoughts (e.g., “I’m still learning this content. It’s going to be rusty and feel clunky – that’s okay!”).

You need to take a deep breath and keep watching because the video will give you valuable feedback.

For example, if you stop midsentence and you don’t know how to proceed, that tells you something: you don’t know this stuff so well! Make a note. This part of the content needs your attention.

Hand your notes over to a friend, parent, or sibling. Now get them to ask you questions on the content.

I sat with my mum and showed her a print out of my slides for a new presentation. The slides were just pictures (no text).

As I went through the slides, I explained the ideas to mum. I made notes of any sections I was rusty on. Mum also asked lots of questions, which allowed me to think more deeply about the content.

When it came crunch time (a few days before the final presentation), I printed out my presentation slides (16 per page) and used each slide as a prompt. I’d look at the slide and say, “What do I need to say here?”.

Sometimes I wrote out what I’d be saying in relation to each slide (without looking at my notes). Then I checked my original notes to make sure I hadn’t forgotten anything.

It’s really important that you don’t skip the stage of checking to see how you went, especially as you become more confident with the content.

At times, I found myself thinking “I know this stuff! I don’t need to check my notes” but then another part would say, “You better just check . . . just to be on the safe side”.

I’m glad I forced myself to check because more often than not I would discover that I had missed a crucial point.

Zines are cute little booklets you can create on any topic you like. They are fun to make, so I thought I’d try making a mini zine on the main points of some new content I had to learn.

I folded up an A4 page into a booklet and then I sketched out the main points on each panel.

I create a deck of flashcards on some key ideas (question on one side and the answer on the back) and then I test myself with them.

I read the question and before flipping the card, I write out the answer on a sheet of paper or say it out loud. Then I check to see how I went.

The beauty of flashcards is they are small and portable (they can easily fit in your pocket or bag). Whenever you have a spare minute or two, you can get a little active recall practice in.

It’s not enough to do active recall just once on the content you need to learn. For best results, you want to practice recalling the information several times over a period of time.

I didn’t follow a strict schedule for the 30 days. I had my notes for each important chunk of information I had to learn pinned to eight different clipboards.

Every morning, I’d pick up a different clipboard and I’d practice that specific content. I knew as long as I’d had a good night’s sleep in between practice sessions that the information was being strengthened in my brain.

Doing active recall is a bit like doing a high intensity workout: it can be exhausting. But you must remember, just like a high intensity exercise session is an effective way to train and get fit, active recall is an effective way to learn. Unlike less effective strategies (e.g., rereading and highlighting), you can learn a lot in a short space of time with active recall.

The key is to expect the process to be a little uncomfortable. Don’t fight the discomfort. If you trust the process and persevere, it won’t be long before you begin to see amazing results.

Just because active recall is challenging to do that doesn’t mean you can’t have fun with it.

Using a combination of different active recall strategies is one way to keep things fresh and interesting for your brain. But you may wish to try the following things to add a little boost of fun to your active recall sessions:

• Use a different type of pen

• Use a different coloured pen

• Change the type of paper or notebook you use (e.g., instead of using lined paper, use blank A3 paper)

• Incorporate movement into your active recall sessions (e.g., walk and test yourself with some flashcards)

• Change your study environment (e.g., go to the library or study outside)

Like I said, active recall is challenging to do, especially when you first start learning new content. You can feel awkward and clumsy. For this reason, it’s easy to make excuses to get out of doing it (e.g., “I’m too tired”, “I’m not ready to do it”, and “It’s not the right time”).

This is where you need to harness the power of habits.

Find a set time in your day to do a little active recall practice. For instance, during my 30 days of active recall, I scheduled my practice sessions for first thing in the morning. I knew after I washed my face, I would sit down to practice.

Incorporating active recall into my morning routine worked really well for me. I was getting the hardest thing done first thing in the day. And once it was done, I could relax. It was done and dusted!

At a certain point, I became more confident with the content and I found I was on a roll. I felt motivated to do active recall.

This is when I started to look for spare moments in the day to squeeze in a few extra mini practice sessions.

For example, one day I found myself waiting in a car. I grabbed a paper shopping bag and started scribbling out the content onto the bag. As soon as I got home, I checked the shopping bag against my notes.

I hope you can see that there’s no one set way to do active recall. This is a highly effective strategy you can be creative with. As long as you’re testing yourself and checking to see how you went, you can’t go wrong.

And if you do make a mistake? It’s no big deal. If you check to see how you went, you won’t embed the error in your long-term memory.

Study is such a vague term.

Many students know they should study, but they’re not exactly sure what study is and what they should be doing.

This is a problem.

If you don’t know what study is and what effective study looks like, chances are you probably won’t be able to do it.

You’ll be winging it.

How can you develop a solid study habit?

I’m going to breakdown what study is and how you can study in the most effective way to optimise learning. I’ll also share a simple way to combat procrastination and kick-start your study sessions.

Study is where you spend time understanding ideas. It also involves cementing ideas into your memory.

Study is different from collecting information (e.g., downloading articles, buying books, and saving videos to watch later). Study involves taking that information, spending time trying to understand ideas, and making connections between different ideas.

Let’s be clear . . .

Study is different from working on homework and assignments.

Homework and assignments are relatively straightforward. The teacher tells you exactly what you need to do. If you’re not sure what to do, you can ask for clarification.

Study is not so clear cut.

Unless you have a private tutor, a friend, or teacher who spells out what you need to do in your study sessions (e.g., “Go test yourself with this flashcard deck tonight and then test yourself again in two days’ time”), no one is telling you what to study and how to do it. This is something you need to figure out for yourself.

The good news is there are simple things you can do to help you pinpoint what you need to study (more on this shortly).

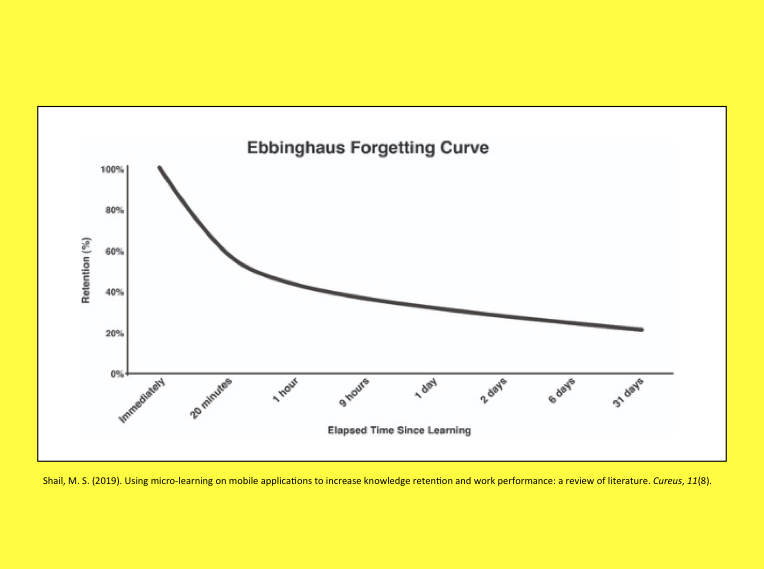

You will forget most of what the teacher says in class unless you make an effort to retain it. This is why study is so important. Study is what embeds ideas into your memory.

In psychology, there’s a concept known as the Forgetting Curve.

The idea is simple: information leaks out of your brain over time. But by studying, you can slow down the rate of forgetting and even interrupt it completely.

Most of us have unrealistic expectations when it comes to learning new ideas and skills.

A lot of students expect learning to be fast and easy like in the science fiction film The Matrix.

There’s a famous scene in The Matrix where Neo gets plugged into the ‘Knowledge Upload Machine’. A floppy disk with combat skills is inserted into the machine and Neo rapidly acquires all the skills of jujutsu.

Many of us want instant results like Neo. If we can’t understand something straight away or nail the skill the first time, we give up.

What do we do instead?

We run to things that deliver instant gratification (e.g., TikTok, video games, and YouTube). These things bring us temporary relief from the negative feelings and discomfort that arise when we are faced with challenging work.

But they also take us further away from our goals.

Here’s the reality of study . . .

Study isn’t easy.

It takes work.

It takes time.

But if you can get yourself to sit down and do a little bit of study every day, you’ll see that over time all those study sessions will add up to something solid.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking of study as being one giant overwhelming task. This makes the work feel scary and extracts all the fun from the process.

When we see study as being overwhelming, we feel stressed and when we feel stressed about any task, we are more likely to procrastinate.

So, let’s break the process down into more concrete simple tasks to make it seem more manageable and less threatening.

Before you sit down to study, set yourself up with the things you need to learn. Get out your pens, paper, notes, textbook, flashcards, a glass of water, post-it notes, noise blocking earmuffs/headphones, etc.

Is there anything that could distract you when you study?

Deal with distractions from the outset. Create a barrier between you and Big Tech (this way it will be hard to run to the fun stuff when things get tricky with your work).

The simplest and most powerful thing you can do is take your phone and place it away from your body in another room. Turn it off or put it on silent.

If there is any visual clutter in your space, collect it up in a box and put it in another room. Being surrounded by piles of clutter can increase your stress levels and make it hard to focus.

Setting yourself up is an important first step for several reasons:

1. It will help you get into a state of flow with your learning;

2. You’re warming your brain up and mentally preparing it to do the work; and

3. You’ll be less distracted which will allow you to learn more in less time.

Once you’ve set yourself up, this bring us to the next step . . .

Select a subject and then ask yourself these simple questions:

1. What didn’t I understand in class today?

2. What topics were confusing?

3. Where are the gaps in my knowledge?

These questions can be difficult to answer several hours after a class, especially if you didn’t take any notes in class.

This is why it’s a good idea to scribble down on a post-it note anything you don’t understand in class. This post-it will help guide your study sessions later in the day.

If you can’t answer the above questions, here are some ways you can gain clarity on what you need to study:

• Check the unit content section of your syllabus. Focus on the content you have already covered in class. If any words are unfamiliar or confusing, that’s a clue you need to study those ideas. Why? Because you’re going to be assessed on this content at some point in the future.

• Test yourself with a practice test, past exam paper, or flashcards. Stumped by a question? There you go! That’s a sign you don’t understand this particular topic so well.

When you realise you’re a bit rusty on a concept or don’t understand something, don’t feel bad. Instead, write the concept on a post-it note and tell yourself “Good job!” You’ve just pinpointed something to study. You’re one step closer to getting a better understanding of the content.

You’ve figured out what you need to study. Now it’s time to decide on the best strategy to learn the content.

The strategy you select will depend on where you’re at on your learning journey and what you need to be able to do with the content.

I see learning as being made up of two distinct parts:

• Part 1: You first need to understand the information and make sense of it

• Part 2: You need to commit the information to memory so you can easily retrieve it when you need it (e.g., in a test or exam)

Doing part 1 well will help you with part 2 (remembering the information). But it won’t be enough to cement the ideas into your memory. You’ll need additional strategies for this.

Here are some ideas to help you with each part of your learning journey . . .

When you are trying to understand a topic

• Grab a sheet of A3 paper and draw out the ideas as you read

• Watch an animated video explaining the topic

• Ask for help from an expert (e.g., teacher), friend, or Google

• Access children’s books or graphic novels on the topic

When you need to remember information on a topic

• Do a practice test

• Teach a friend, a pet, or the wall

• Write or draw out as much as you can remember

• Record yourself explaining an idea

If you want to remember something, you need to practice remembering that information.

It’s okay to incorrectly recall the information but it’s critical that you find out what the right answer is immediately. If you do this, you won’t embed the incorrect information!

Steer clear of studying in the following ways:

• Passively rereading your books and notes

• Highlighting your notes

• Copying out your notes

• Summarising your notes or a chapter (this is worth doing in the early stages of learning something new but it’s not a good way to prepare for a test or exam).

These are what I call ‘Feel Good, Get Nowhere’ study strategies. They feel good to use because they’re easy. But they get you nowhere because they’re not very effective ways to learn.

We live in an environment that has trained us to seek out pleasure and immediate gratification. This makes sitting down to study incredibly difficult for a lot of people.

Study forces us to face up to the fact that we don’t know everything and/or we may suck at some things (at least to begin with).

This explains why you probably won’t feel comfortable when you first sit down to study. You’ll feel the urge to distract yourself. But resist the urge.

Sit with the discomfort. Don’t run from it. Push through it.

Use an electronic timer to time your study sessions (25 – 45 minutes). This way your brain knows there’s an end point and you won’t be stuck in the discomfort forever.

When the timer goes off, give yourself a break. These breaks will help you to mentally re-energise.

A recent study from the University of Sydney confirmed this. Researchers found taking a five-minute unstructured rest break improved students’ ability to focus and learn.

Force yourself to step away from your computer screen and go outside. Look up at the sky and some trees. If you can, add some movement into your breaks.

You are not a machine. In order to engage in quality study, you need to take regular breaks.

We’ve just broken down study sessions into five simple steps:

Step 1: Prepare your environment

Step 2: Pinpoint what you need to study

Step 3: Choose your study strategy

Step 4: Embrace the pain and go!

Step 5: Take a break

Your first few study sessions will require a bit of willpower to carry out. But why would you want to rely on your willpower reserves all the time?

That’s far too draining.

This is where creating a study habit can help to streamline the process and conserve your mental energy.

Most of us have easy access to an abundance of endless entertainment options. There are many cues in our environment that remind us of the fun things we could be doing instead of study.

If you can establish a study habit, you eliminate all these options from your life for that part of your day.

Once you decide when and where you’re going to study, you’re no longer overwhelmed by all the choice. Your brain knows exactly what it needs to do.

Here are some examples of tiny study habits:

1. After I have a snack, I will take my phone and place it in another room (on silent).

2. After I finish dinner, I will take out my flashcards and place them on my desk.

3. After I unpack my bag, I will grab a post-it note and ask myself “What didn’t I understand in class today?” I will write down one thing.

4. After I have a shower, I will place my textbook on my desk.

5. After I hear a concept I don’t understand, I will write it down on a post-it note.

6. After I have pinpointed what I need to study, I will ask “Which strategy will I use to learn this?”

7. After I hear the timer go off, I will get up and go outside.

These study habits are tiny but that’s the whole point. When we are starting out, we keep the study behaviour small so it feels fun and easy for the brain.

“Study” can sound mighty grim. It can bring to mind images of staying up late into the night cramming. It can feel repetitive, dull, and pointless.

“Study” sounds like what your teachers and parents want you to do. It doesn’t sound like something you’d do for fun.

Frankly, the term “study” comes with a lot of baggage.

But that’s okay. There’s no reason why you need to use the word.

You can create a mind map or test yourself with a flashcard desk without calling it “study”. Just do the tasks you need to do to understand and remember the information. There’s no need to name the tasks as “study”.

If you do want to call it something, try using a fun and playful term that has no baggage. For example, you could frame study as doing bicep curls for your brain.

Think about the things you are good and confident at doing now. What were you like when you first started? You probably weren’t great!

But you kept at it and over time, you got better. Your skills and confidence developed.

The same thing applies with study. You’re not going to be amazing at studying to begin with. You’re going to feel awkward and clumsy as you wrestle with new ideas. But cut yourself some slack.

Approach your study sessions as mini experiments. Go into them thinking, “Let’s test out this strategy and see how it goes”. If it doesn’t work, you can try again or try something different in your next study session.

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive sessions on learning to learn, combating procrastination, exam preparation, how to focus in the age of distraction, habit formation and much, much more!

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to our newsletter:

© 2024 Learning Fundamentals